ON THE EDGE

|

| Die Schlacht am Stoss, 17 June 1405 According to legend, the Appenzeller spouses arrive in time to save the day (upper left) Litography after painting by Martin Distell |

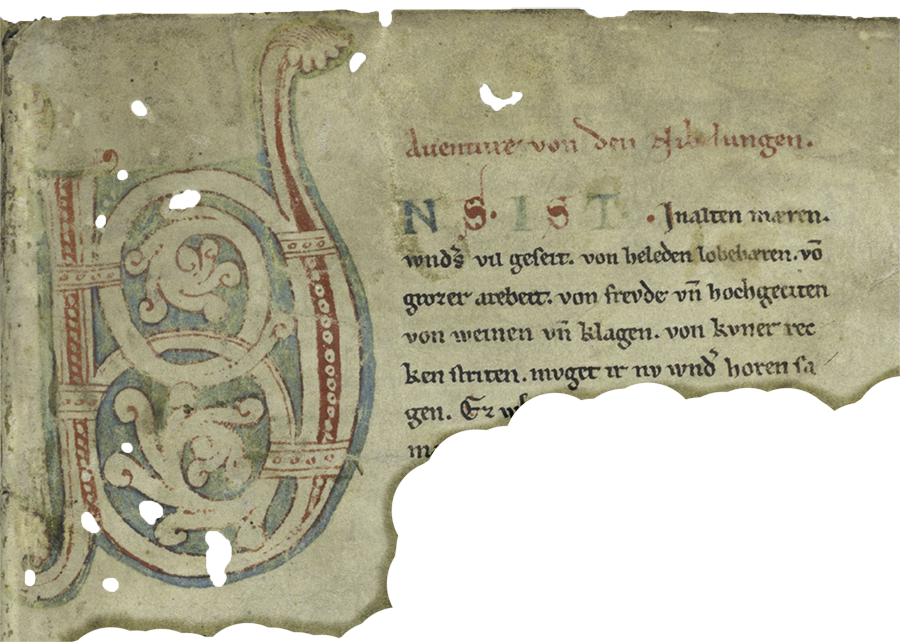

Twenty years ago, I went on a pleasure trip to Appenzell Innerrhoden, the Swiss Canton bordering on the Alpine Rhine. I had been there already once before to do some serious hiking in the Säntis Mountains (A River Runs through It), but this time had a more leisurely walk in mind. The starting point was a small town called Gais, from where the plan was to eventually reach Brülisau at the foot of Säntis. At the small B&B I was staying, I could not help observing an intriguing picture hanging in the vestibule. Warriors were hacking at each other in a confused pêle-mêle, but, more interestingly, behind heavy clouds on the uphills, you could glance an apparition: a cohort of women in white shrouds, brandishing clubs, scythes and sickles as threatening weapons.

Besides noting the charm of a tale, where peasants were being onset by their overlords in a minor skirmish, only to be saved by their spouses, I gave no further thought to this scene, being occupied with planning the following day's activities. Little did I know that I was actually looking at a decisive battle between some 1500 heavily armed knights with foot-folk and only some 400 Appenzeller peasant infantry, with repercussions that eventually would almost extinguish the House of Ems and seriously disrupt the House of Habsburg.

How come that a regular army of knights was needed and put together in 1405 to besiege the sparsely populated Appenzeller region, and why did this minor battle have so grave consequences? To answer these questions we have to backtrack some fifty years and recapitulate events on the Alpine Rhine and adjacent regions post the terrible catastrophe of the Black Death.

The decades immediately following the mid-fourteenth centrury (with its grave bloodletting) were dire indeed. Whole landscapes lay deserted with few left to till the land. For the surviving few, harvests were hard gained and meager, with a serious dearth of labour and the climate getting more hostile by the year. Landlords had to watch their wealth dissipating like sand running through powerless fingers and their hold being loosened on the few indentured servants left who could help claw back a meagre part of it. Rather than stay on domains that hardly could feed the landlords, not to speak of their servants, the latter often preferred to migrate towards the few cities then in existence, in the hope of gaining their sustenance under better conditions.

|

| Source: Wikipedia |

Hardly surprising, lesser nobility on the Alpine Rhine, as in the rest of Europe, suffered greatly from these changes, many of them having to forego their domains and meeting oblivion. The Emser, being part of this suffering class, barely managed to hold on to their possessions. Still, they were lucky insofar that a younger generation, consisting of brothers Rudolf II (1319-1379), Ulrich II (1323-1402) and Eglof (1331-1386) von Ems could take over after the Plague. But, whereas the Emser during the first half of the 1300s had started to embellish their holdings, by rounding up their domain in the immediate neighbourhood of fortress Hohenems and by acquiring domains in the vicinity, mostly within Dornbirn and Feldkirch, but even across the Rhine, such activities came to a standstill after the Plague.

In contrast to this, the grandees of the Kingdom could take advantage of lesser nobility's dire conditions and continue to consolidate their holdings by appropriating domains that lesser landlords had to let go. Within the region, the Habsburger were the prime actors, rather agressively pursuing a policy of land acquisition and consolidation. The strategy was, firstly, to create a link between their Duchies of Austria, Styria and Carinthia on the one hand, and their possessions in Swabia and Southwest of Lake Constance on the other, and, secondly, to embellish and consolidate the latter into a contiguous régime (from a motley of domains with various rights of ownership) so that, hopefully, a resemblance of the Swabian Duchy of yore (A river runs through it) could be re-established under Habsburg.

The first part of the strategy was successful. Already, in 1363, Tyrol became a Habsburg possession, and, between 1363 and 1394, the major part of the lower Alpine Rhine on its right hand side fell under their suzerainty. This established a link to the Habsburg possessions in Swabia and present day Switzerland, but had also the effect of encircling the Emser domains in Hohemems and Dornbirn. From then on, the Emser had, nolens volens, to throw in their lot with the Habsburger. Junior family sons went into these garandees' service, as governor of domains on the Alpine Rhine, as well as further East, and even as court officials. The senior Emser, in their position of Imperial Knight, felt obliged to participate as ally in Habsburg campaigns to the West of the Alpine Rhine.

On the other hand, the Habsburg strategy to consolidate their Western possessions ended in disaster. Despite early success, mostly in Swabia, resistance to the Habsburg actions increased steadily in what is now Switzerland. Major cities in the region, that is, Luzern, Zürich and Bern, saw their own ambition to enlarge their respective influence sphere stymied by the Habsburg expansion, and responded in turn by aggressively encroaching upon Habsburg domains in their vicinity. Although their expansion mostly contravened the feodal laws prevailing at the time, the Habsburger Duke Leopold III found it difficult to enforce the legal right to his domains, since he lacked support from the reigning King Wenceslaus of the House of Luxembourg (who resided far away, in Prague).

|

| A covetous Duke ... ... fights to the bitter end Source: Österreichische Nationalbibliotek |

As a result, several small conflicts broke out between the Duke and the cities, the latter then already in alliance with the (original) Eidgenossen. Matters came to a head with the Sempach War, when an army of knights, led by Leopold III himself, met infantry from Luzern and its Eidgenossen allies at Sempach in 1386 and was completely annihilated. Two Emser, Eglof and his younger nephew Ulrich III (1345-1386), son of Rudolf II, died in that battle, as did the Duke himself. From then on, the Habsburger were on the defensive in Switzerland. The resulting peace was fragile, and conflicts kept blossoming up over and over againg amid periods of uneasy truce.

|

| The Battle of Sempach (1386) Schilling (1485), Spiezer Chronik Source: Burberbibliotek Bern |

During the following two decades, broad swathes of Habsburg land were lost to the ever more powerful Eidgenossen. This did, however, not affect the Emser which, located mostly to the right of the lower Alpine Rhine, felt safely ensconced within Habsburg lands. By entering into the service of the Habsburger, the Emser foresaw to regain their former wealth. At least, this is how it looked to them. Instead, the voracious Western neighbours would come to threaten also their home domains.

|

| Battle Chapel at Sempach. Shields of the two fallen Emser within the red frame to the left. Photographer: Boris Bürgisser |

In 1404, a new conflict arose on the Swiss plateau, in the immediate Western vicinity of the Alpine Rhine. Since centuries back, the Abbey of St Gallen, an Imperial Principality, had colonised a large piece of land to its South West. The region's name, Appenzell, stems from the Latin "Abbatis Cella" (The Abbot's Dependancy). In the rich and fertile times prior to the Plague, the peasants in this land had increasingly been granted self-rule. Alas, in the bad decades following the plague, the Abbey attempted to claw back its traditional rights to the land and levies on its peasants. In reaction, the Appenzeller allied themselves with the Eidgenossen and the town of St Gallen and refused to rescind their acquired rights.

The Abbey was in turn allied to the Habsburger and asked them for aid. Duke Frederic IV, son of Leopold III and Lord over Tyrol and the Western Habsburg domains, assembled an army, consisting of his house troupes and independent knights from Swabia (including the Lower Alpine Rhine), and started a punitive expedition against the Appenzeller. On June 17, 1405, his army ascended the steep and high incline towards the Appenzeller Plateau from Altstätten, a domain broadly opposite Hohenems across the Rhine. It was a rainy day and the incline slippery, so the cavalry had to dismount in order to manage the climb. Just at the plateau rim, at a pass called Stoss, the Appenzeller ambushed the allied army and managed to annihilate a major part of it, with the remainder stumbling back down into the Rhine valley, hugely demoralised, never to return.

|

| Die Schlacht am Stoss Schilling (1485), Spiezer Chronik Source: Burgerbibliothek Bern |

Greatly encouraged by this success of a peasant army over a heavily armed knightly compound, the Appenzeller hordes streamed down from their highlands and, in the following two years, managed to occupy most of the lower Alpine Rhine region. Castle after castle was subjugated, the noble families expelled and the cities and peasants encouraged to revolt and join the party. As a result, the region was reorganised into the so-called Bund ob dem See (League on the Lake [of Constance]), a kind of miniature Eidgenossen, which threatened feodal rulers as far off as even Tyrol and Southern Swabia.

Among the nobles most affected were the Emser. Goswin V (1372-1405), Georg and Wilhelm von Ems died at the Battle of the Stoss, all being young cousins of Ulrich III (who had died already at Sempach). Goswin's two brothers Marquard III (1360-1414) and Ulrich V (1364-1430) von Ems, who resided at the family seat at Hohenems, were besieged early in 1407, and both castles on their domain, the fortification of Hohenems, as well as their smaller residence castle Neuems (also called Glopper) burned to the ground. They were lucky just to escape, leaving all their belongings behind to be plundered by the Appenzeller, and their domains to be expropriated and incorporated into the League.

Even if the Appenzeller reign did not survive more than another year, the League of the Lake being abolished in 1408 by an alliance of Swabian knights (among them the Emser) after the Battle of Bregenz, and status ex quo ante re-established, House Ems was at the very low point of its existence so far. It took more than 15 years to rebuilt the smaller Castle Glopper alone, and huge loans had to betaken out to finance restauration full-out.

|

| Duke Frederic IV |

Whilst Johannes XXIII had hopes that the Council would acknowledge him as the true Pope, it soon appeared that the Assembly preferred all three contenders to resign and that a one and true new Pope be elected. Duke Frederic IV, who was Johannes' ally, helped him escape the Council and reside in his own domains in Swabia. For this, the duke was severely punished, by the Council as well as by King Sigismund. The latter issued an Imperial Ban over him, which implied that all his lands were forfeit and returned to the King as Imperial domains.

|

| King Sigismund arrives at the Council of Constance Ulrich v Richental (1440), Chronik des Konzils von Konstanz Source: Österreichische Nationalbibliotek |

Apart from the heartlands of his realm, mainly the County of Tyrol, he lost all other possessions in the West. The Eidgenossen made haste to "liberate" all Habsburg lands in present day Switzerland (without handing them over to the King, thus rendering them, nolens volens, into Imperial lien), whereas all domains in Swabia, including those on the Alpine Rhine, were formally redistributed by the King as "Pfandherrschaft" to some trusty followers. Even in Tyrol, Frederic had to fight hard to prevent the County being taken over by rival nobles, so the Western House of Habsburg was in deep disarray. Ever since these unfortunate years, the Duke is better known by his nickname "Fred with Empty Pockets" (Fridel mit der leeren Tasche).

Best we stop here, lest you be led into deep depression over the overall morosity of the tale, Dear Readers. The more so, since the age of conflict and war will not end with these ruinous outcomes. So, arm yourself with courage, whilst awaiting the next post in this blog series!

Comments

Thank you kindly for your encouraging and generous comments.

It is indeed true that the major efforts spent on this blog consist of distilling out, for each blog post, a few paragraphs from an enormous and bewildering amount of historic details. I am lucky insofar, as the history of the House of Ems is underpinned by an impressive number of history books and monographs. But they, too, excel in detailed descriptions, year by year, of the family's fate, with all possible details about family members and their dealings. After having finished each post, I get busy reading, for a month or so, all the sources relevant for the next post. At my age, I am forgetting almost immediately what I am reading and getting more and more depressed by the task at hand. Finally, I give up and simply start writing the tale, only vaguely remembering what I should put on paper. To my surprise, the unconscious has somewhat digested all these details and out from my pen comes something that seems rather reasonable. So I usually make hast to publish it, after just checking that I got the few facts and years quoted right. Permit me to add, that Google (the German version) contains an amazing amount of historical details, which sometimes comes in handy, when I just need a freshening up of the complicated facts I already have digested (and forgotten) from the historical treaties.

Yours sincerely

Emil