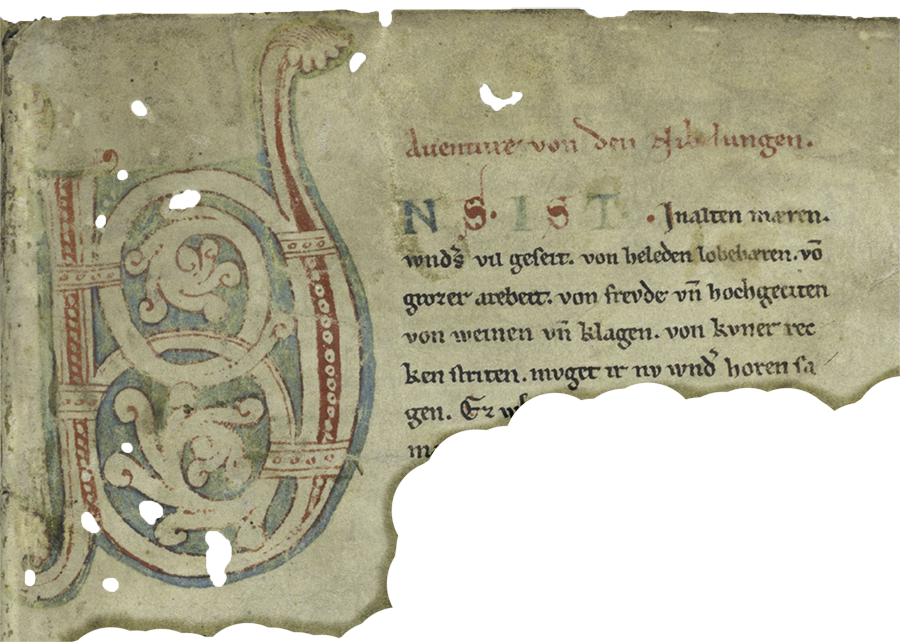

UNS IST IN ALTEN MAEREN ...

For those of you unused to reading Middle High German, an English interpretation of the first line in the above parchment is as follows:

To us, in olden stories are many wonders told

This strophe gives us the introductory words of a famous epos. It was written down for the first time in the late 1100s. The words spell it out clearly that the oeuvre in question is based on a manifold of different songs, performed by minstrels at chieftain halls, noble houses, royal residences and imperial courts throughout the ages.

I am of course referring to the Nibelungenlied, the beloved common inheritance of all the Germanic speaking peoples, all 100 million of them, which populate the continent, from the Dolomitan spires in the South to the Cape of the Thundering Waves in the far North, from the wooden Carpatian rises in the Southeast to the Ice and Fire of the lonely island to the far Northwest.

The line quoted above alludes to a universal truth about the great eposes of yore: they were formed in a time of oral tradition, grew organically over the centuries, until, finally, a scribe or poet took upon him the task of putting them into unified metric. Till then, facts and episodes were added to it, like year rings on an age old oak, by each new singer learning it by heart from his master and embellishing it on his own. Over the centuries, facts and episodes turned into fiction and fiction turned into myth. Thus, each epos contains a myriad of bits and pieces of the real world, amalgamated into the shape of the great oeuvre we get to know and learn to admire in our times.

To me, this process appears also as an apt metaphor for how the human mind works and creates its awareness. Ever since early childhood, observation upon observation is loaded into the synapses of the brain, everything being pressed into the myriad of nerve strings. Over time, amalgamation takes over, just as in the oral tradition of eposes, until facts distill into memories, memories into anectodes and anectodes slowly fade away into oblivion.

As a quirk of nature, outside stimuli, through taste, smell, spoken words or other inputs can re-awaken long-submerged observations, which can come back to us with a vengeance. Just recall the famous Gâteau Madeleine cake that got Marcel Proust going down memory lane. For me, this brings to mind a similar incident, which will branch out into several stories, I am afraid, before this blog post comes to its long sought end!

|

| View of Dürnstein Copperplate by Matthäus Merian, in Topographia Provinciarum Austriacarum (1679) |

In the late 1990s, I was working at the Federation of Swedish Industries, with the task of co-ordinating the Federation’s policy vis-à-vis the common European currency (as an aside, the predecessor of the EMU was called EMS [the European Monetary System], which always brought a smile on the face of any new acquaintance I was presenting myself to in the Federation).

Those working years were intensive, so I was glad to take a short vacation in my old homeland in Summer 1997; I rented a room in Dürnstein in Wachau and spent a week cykling the nice surroundings there. Dürnstein lies on the Danube river some 100 kilometers West of Vienna. The river runs rather narrowly there; a castle ruin reminds of the old days of taking toll of ship traffic, since narrows made it easy to install a barrier on the river. The former castle is also famous for having held King Richard Lionheart captive for a time, before his delivery to Emperor Henry VI in Speyer (see Once upon a time).

One day, I took a longer bycicle tour all the way to the town of Melk, to visit its famous (and splendid) abbey. The trip and visit took most of the day, so I was glad to take the line-boat down-river the Danube back to Dürnstein. On the boat, there was a map, on which all the stops along the boat’s itinerary were listed, ranging from Passau to Vienna. One stop, the one just before Melk, caught my attention. Could it be? Indeed it could! The town’s name was Pöchlarn! Suddenly, the brain lit up and an old rhyme re-emerged from the unconscious.

|

| Excerpt from the Nibelungenlied, Codex A (late 1200s) Source: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek |

Then spake to the Burgundians the gallant knight and bold,

Ruediger the noble: “Now let us not withhold

The story of our coming unto the Hun’s country.

Unto the royal Etzel might tidings ne’er more welcome be.”

Down in haste through Osterich the messenger did ride,

Who told unto the people soon on every side,

From Worms beyond Rhine river were high guests journeying,

Nor unto Etzel’s people gladder tidings might ye bring.

Interpretation: George Henry Needler

For those of you not familiar with the exact content of the Nibelungenlied: Ruediger von Bechelaren is King Etzel’s Margrave, that is the knight guarding the borderland towards the Germanic peoples to the West of the “Huns’ country”. The three Burgundian Kings, called the “Nibelungen” in the epos have, after guesting the Bishop of Passau, passed through a dangerous no man's land at the border. After fighting back several deadly assaults there, they finally reach the Margrave’s domains and are treated by Ruediger as honoured guests in his fortification Bechelaren (present day Pöchlarn). From there, the Margrave accompanies the company the Danube down-streams to Etzel's capital, but not before sending ahead messengers to the King, as is told in the strophes cited above.

|

| A no man’s land crossing the Danube? |

Surprised to find that the mythic Bechelaren had a real present day counter-part in Pöchlarn, and curious about, whether the border region of the epos was based on historic facts in turn, I did some research on the issue when back home in Stockholm. The results surprised me and led me to a deeper understanding of how millenia-old eposes grow and ripen.

It turns out that there indeed had been such a no man’s land between the settled Germanic peoples in the West and nomadic peoples in the East, albeit the Huns were not involved. This border came to be almost two hundred years after Attila’s (King Etzel in the saga) death. In the void left after the Romans had vacated the Danube settlements in 488, eventually Bavarian tribes had moved in from the North and Awar/Slavic peoples from the Southeast. For two hundred years onward, they were separated by this border, indeed some kind of no man’s land with a breadth of over 50 kilometers across river Danube.

Charlemagne put an end to this state of affairs, when he annihilated, in his Awar campaigns 791-97, the Awar peoples and incorporated their lands, ranging all the way to Lake Balaton in the East, into his Caroline Kingdom. As governors for this newly conquered region, called Marcha Orientalis (the Eastern Marches), margraves were installed, among them the governor of the Danube region.

|

| Battle against the Avars Stuttgarter Psalter (ca 830) Source: Württembergische Landesbibliothek |

A hundred years later, a new nomadic people, the Magyars, stormed in from the East and grabbed, in 907, the Danube region almost to Passau in the West. Interestingly, the Hungarians did not fully replace the Bavarian order in their newly conquered territories, some lords could keep their properties under Magyar leadership. There was even a Bavarian margrave as governor of the Hungarian Danube region for a time.

It took more than fifty years of constant fighting to push back the Magyar bulge on the Danube. Eventually, King Otto the Great of East Francia could stem the flood, at the great Battle of Lechfeld (955). Thereafter, the Magyar backed off a bit Eastward, whilst still holding fort in the region around present day Vienna.

|

| The King fights the Hungarians Sächsische Weltchronik (ca 1270) Source: Forschungsbibliothek Gotha, Universität Erfurt |

Finally, in 976, King Otto installed Luitpold the Babenberger as margrave of the reconquered areas along the Danube located East of the ancient borderline. It was just a small splinter of the Marcha Orientalis of yore, eventually to be called “Ostarrichi” (Marcha Orientalis in Old Bavarian). The margrave’s seat was, at the outset, in Pöchlarn, but would soon be moved to Melk. In the century that followed, the Magyar were thrown back behind the river Leitha and Vienna eventually arose as the new centre of Ostarrichi.

|

| View of Pöchlarn Copperplate by Matthäus Merian, in Topographia Provinciarum Austriacarum (1679) |

The Nibelungenlied was put in writing first in the late 1100s, some two hundred years after the above “reconquista”. Thus it does not surprise us that facts got a bit mixed up by the performers of the epos and ultimately its author. There was indeed a germanic (Bavarian) margrave under nomadic rule, but he served under the Magyar, rather than the Huns. A margrave indeed had his government located at Pöchlarn, but he was guarding the border Eastward, rather than Westward, and had a germanic (Bavarian) duke as overlord, not a nomadic one.

To our regret, though, it proves impossible to present any historic underpinning to the name of Ruediger; its origin remains submerged in the murky sea of the past. This is surprising, since most of the notable heroes in the saga can be traced back to real persons. To name just a few: Gunthar – Gundahari, King of the Burgundians; Dietrich von Bern – Theoderic the Great, Ostrogoth King of Italy; Etzel – Attila, leader of the Huns; Kriemhild – Ildico, Attila’s second wife; Pilgrim, Bishop of Passau. We may assume that Ruediger was introduced at a late stage of the epos’ gestation, no doubt conceived by the singers of the high middle ages, in the times of courtly (and knightly) chivalry (in the arts, if not in real life).

On the surface, Ruediger is just a side show in the story, compared to the notable heroes and heroines dominating the scene. He turns up first in the context of King Etzel’s marriage plans, when he travels to Worms as the King’s representative to propose to Kriemhild, widow of Siegfried the Dragonslayer. In order to woo Kriemhild, who is reluctant to be wed into foreign and heathen lands, he swears a holy oath of fealty, to always stand by her in her future life in the Huns’ land.

|

| Kriemhild bids welcome to Ruediger von Bechelaren in Worms Der Rosengartt vnd Lucidarius (1420) Source: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg |

He next appears when, many years thereafter, the Nibelungen are welcomed in his domains, after they have crossed the no man’s land East of the “Huns’ land”. They enjoy his reknowned hospitality for many weeks before continuing their journey to Etzel’s court. Ruediger goes as far as giving away his daughter in marriage to Giselher, the youngest of the three Burgundian kings.

|

| Ruediger bids welcome to the Nibelungen in Bechelaren The Nibelungenlied (1440), Hundeshagenscher Codex Source: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin |

Finally, he plays an important part in the terrible mutual slaughtering of Nibelungen and Huns, in the great hall at Etzel's court. Ruediger first attempts to keep himself and his men out of the conflict between the two groups. However, as soon as the Nibelungen kill off Etzel’s son, the King first asks and then commands his margrave to join the battle. Still, Ruediger is reluctant and would prefer to stand aside, bound as he is by his bond of friendship with the Nibelungen, not least through the marriage of his daughter to Giselher. He is caught in an unsolvable conflict between that bond, on the one hand, and his oath of fealty to the King as well as to Kriemhild on the other.

Finally, he gives in and joins the slaughter together with his men. In the mêlée, Hagen von Tronje, who has lost his shield in the tumult, reminds Rüdiger of his bond of friendship and asks the margrave to yield his own shield to him. Giving in to his fate, Ruediger complies and continues to fight unprotected. Thus, he willingly chooses death as the solution to his distraught.

|

| Ruediger hands over his shield to Hagen The Nibelungenlied (1440), Hundeshagenscher Codex Source: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin |

I have always been fascinated by the fate of this knight with his terrible conflict between loyalties, which could be resolved only by deliberately seeking death. In the epos, this side story is presented in such a clear and lucid form, depicting Ruediger in an almost three-dimensional fashion with his internal conflict, that it puts weight to my view that his story must have been added late in the gestation of the epos and could well constitute a poetic addition made by the author himself, when finally putting it in writing.

-o-

The reader may well ask why the above ramblings are being included as a post in this blog, which after all deals with the history of the House of Ems, rather than with heroic personalities in an ages old epos. Well, it turns out that the Emser are very much involved; not in the epos itself; rather, in its safeguarding and preserving it for posterity.

Although the Nibelungenlied was popular in medieval times, with many a handwritten copy produced well into the 1400s, it went out of fashion during the Renaissance and its existence was essentially forgotten. Only bits and pieces from it survived as popular tales, but the great oeuvre had exited from the limelight.

After three hundred years’ hibernation, the epos was finally re-awakened. It took three valiant men to accomplish this task. The first to name is Johann Jakob Bodmer (1698-1783), philologist and professor at the Collegium Carolinum in Zürich. In the good professor’s view, the poets and epicists during the High Middle Ages were the true founders of German literature. In particular, the writers from the region of Swabia had, during the age of the Staufen rulers, risen to the zenit of artistic fulfilment.

|

| Three men to find the “sleeping beauty" |

He dedicated his life to recover original manuscripts of the time. Among others, he queried the archives of Hohenems for a manuscript he had heard rumours about, a complete recording of an ages old epos, the Nibelungenlied. To his regret, the owner of the Hohemems library, Count Franz Rudolph von Hohenems (1686-1756) refused him access to his collections.

To the rescue came a surgeon from the town of Lindau, close to Lake Constance, who also delved into writing and philosophy. Jakob Herman Obereit (1725-98), that was his name, was one of Bodmer’s admirers. Upon hearing about the professor's bad luck with the count, he took upon himself to help him out. Said and done, he travelled to Hohenems and paid a visit to his relative, Franz Joseph von Wocher (1721-88), a poligot and art collector, and also at the time administrator of the Hohenems domain in absence of the count. Franz Rudolph was being kept busy at the time (1755) with preparing his men for war against the Prussians, in his capacity of field marshall and commander in chief of the Habsburg army in Moravia.

The two cousins perused the library at Hohenems Palace. At long last, two leather bound volumes caught their eye. The first carried on its initial page the title “aventure von den nibelungen”, to the delight of the two treasure hunters (the second volume contained the epos “Barlaam und Josaphat” by the author Rudolf von Ems).

Without the count’s knowledge, both volumes were sent to Bodmer as a loan. The latter transcribed the latter half of the Nibelungen “aventure” and published it in 1757. Many years later, in 1779, the professor regretted this incomplete publication and contacted again Wocher with the plea that he recover the manuscript a second time for a comprehensive transcription and publication.

Wocher, by then already retired, travelled a last time to Hohenems and found the library in a rather desolate state (the last count had died already in 1757). Still, he could dig out, from under a mouldering heap of pergaments and palimpsests, a manuscript of the Nibelungenlied, which he sent to Bodmer. It turned out that it was another version of the opus. Later on, it was called Codex A, in contrast to the first discovered version, nowadays called Codex C.

Bodmer thought that Codex A was the original manuscript, originating from the author himself (thereof the denomination “A"). But later research located yet another complete manuscript, subsequently called Codex B, which could be considered as the version closest to the original. Its beginning strophe is different; it starts directly with addressing Kriemhild, the epos’ heroine, omitting the elegant introduction presented at the beginning of this blog post.

.

There once grew up in Burgundy a maid of noble birth,

Nor might there be a fairer than she in all the earth

Interpretation: George Henry Needler

Whatever version be the most authentic, it is clear that all three are needed to provide us with the full story of the Nibelungenlied. The epos now is lodged firmly on the Parnassus, not only in Germanic fields, but indeed all over the literate world. The trinity of codices has even been declared a “World Heritage” by the UNESCO in 2009.

This leaves us with the question, how on Earth the Nibelungenlied found its way to Hohenems. Several theories have been put forward in that regard. At the outset, there was a view that the epos could actually have originated from the domain of Hohenems; even that it could have been authored by Rudolf von Ems himself (see Ars gratia artis), a famous epicist of the High Middle Ages. This was, of course, a conjecture too good to be true. The fortification Hohenems was burnt down several times since the late 1100s. No manuscript preserved therein could have survived, especially in view of the last pilfering and burning down in the Appenzeller War (see On the edge), in 1407.

|

| Bishop Wolfger von Erla Source: Diocesan Museum at Udine |

Modern research has resulted in the most plausible conclusion, that the epos has been authored and produced, towards the end of the 12th century, in Passau, under the patronage of Bishop Wolfger von Erla (1140-1218). This so, since the epos in its second half includes geographic and “historic” details about the Daunube region, which only an author well acquainted with the region could have provided. Furtherermore, a bishop of Passau, by the name of Pilgrim (+991), plays an unwarranted prominent role in the story, no doubt due to the author wanting to please his mecenate.

The Bishop certainly must have ordered several copies of the original manuscript to be made, as gifts to his prominent peers, first among them the King and the Duke of Swabia (both of them being of the ruling Staufer dynasty). Those had certainly copies made in turn. The three surviving full codices (A-C) are most probably among those third generation copies. All three have a notable Alemanic tang in their language, caused by the Swabian scribes, who tended to “adapt” language to their liking, while copying.

As to the Hohenems library, it is well established that it was founded by Imperial Count Jakob Hannibal I von Hohenems (1530-87). His brother Merk Sittich III von Hohenems, one of richest cardinals of his time, had built him the palace in Hohenems and it is rather obvious why the lord of the manor felt the urge to embellish it with paintings, gobelins and books. He certainly had the means necessary to that effect. The Nibelungen manuscripts were but a small part of a great collection of books finding their home in the Palace Library.

|

| The last remains of a once great library As seen and photographed at Palace Hohenems |

This is as much as we can find out about the fate of the Nibelungenlied. But I hope you don’t begrudge me a last remark, to polish off this over long blog post:

Is it not an irony of history, that a fierce warlord, responsible for the death of tens of thousand of people, and the devastation of large swathes of land all over Europe, should become the patron responsible for preserving a World Heritage for posterity?

-o-

An old friend of mine, Hermann Becke has made me aware of the fact that there exists a video with a performance of the Nibelungenlied. Very interesting, in particular, since the music for the epos has been lost. But it can be reconstructed, taking preserved tones from old French and Middle High German songs as basis. So, please take the time to listen to the first chapter (“aventure”) of the Nibelungenlied, performed in the same way as medieval minstrels did at the noble courts of yore!

Comments

Richard

Herzliche Grüße

Hermann

Skall läsa mer om Niebelungenlied. Vi läste ju om detta i skolan men har inte hört om dem sedan dess! Och det var ju väldigt länge sedan!

Wagner was not interested in the epos at all. The parts occuring in his operas just constitute a couple of pages in the epos, which after all counts about 300 pages. It is only the first half of the epos that deals with matters at the Burgundian Court in Worms on the Rhine. The other half deals with the Burgundian kings and their tross travelling down the Danube to the country of the Huns, led by Etzel (that is, Attila). They all come to a gruesome end at Etzel's court, after a terrible slaughter.

There is an interesting background to this story. The Burgundian tribe actually used to live on the Rhine around Worms, as a foederati to West Rome. However, the Roman general Aëtius annihilated them in one of his campaigns, with the Huns as help troupes doing most of the job. That was in 437.

The Nibelungensong is a treasure chest for history buffs!

Yours sincerely

Emil

Thank you kindly for the reference to this unique performance. I made haste to include it in the blog post, so that the viewers have easy access to it.

Yours sincerely

Emil

I remain in awe of your diligent scholarship. Through your riveting story-telling, you certainly show that you are a true ancestor of these bards and conservators.

I also wondered about the connection with Wagner's work. Glad to see it referenced. And the singer was also a most welcome coda to your post.

By way of a personal curiosity, my "Playa Name" (used at Burning Man and with other Burners) is Pilgrim.

Stay well and keep up your great work.

Kathy

I watched Eberhard and his fascinating instrument. He explained it but I did not understand Swedish. It was still interesting. Thanks. Jerry Fitzpatrick

Thanks a lot for your kind comment. Actually, I learned most of the content already in highschool, since the Nibelungenlied is THE epic song of Europe (a bit like BEOWULF for you Anglosaxons). The historic links i just guessed on my own and found them to be accurate when checking the facts on internet. Finally, the connection to the Emser library is well known and I discovered it already some years ago. A pity you do not speak German, the singer in the video has done a marvelous job of presenting the Nibelungenlied and explaining the instruments in use at the time it was sung.

Yours sincerely

Emil

Sehr interessante Artikel, Geschichtsbeschreibungen und spannende Reportagen hast Du verfasst, da liegt viel Arbeit dahinter. Einiges hast Du mir ja schon erzählt.

Das Stift Melk ist ein unglaublich interessanter Bau, ich war schon ein paar mal dort. Dürnstein war eine schöne Burg, leider haben die Schweden alles ruiniert.

Zwei Geschichtsbücher habe ich, da bin ich immer wieder beim lesen weil mir neues in der europäischen Vergangenheit einfällt, das ich dann gleich wieder nachlese.

Bleib gesund und freundliche Grüsse

Jochen

It was so good to hear from you. I was already missing your messages and stories.

I am interested in The Song of the Nibelungs, too. Especially in the Ring part. I saw with husband Wagner´s Parcifal more than ten years ago. It made a great impression on us and afterwards we joined an association called Wagner´s friends in Finland. This association is actually the biggest Wagner association outside Germany. We have seen a number of Wagner operas in Europe. I have seen the Ring 6-7 times and every time I find something new it. The music is fascinating and the German libretto is like poetry. Wagner has a certain reputation but I think that it is not his fault that Hitler liked his music. I like his music but not his personality.

We had the chance to visit Bayreuth in 2019 and we saw Lohengrin and Meistersingers. Last summer we had managed to buy tickets to three operas, but unfortunately I got sick just before the flight to München. I felt very unlucky because I had managed to avoid corona for two and half years and then I got the flu just before our trip to Bayreuth..

All the best! Take care!

Kirsi

Very nice to hear from you again and that the blog post was to your liking. Wagner is indeed a capturing artist and he did wonders with the Nibelungen saga. Having said that, the Nibelungenlied, as it emerged in the late 1100s, has a much richer story than the one told by Wagner. Wagner's tale encompasses just a few pages in the whole epos, which deal with the old myths of Siegfried, the dragon and the treasure of the Nibelungen. Wagner embellished those parts with a lot of "Germanic" olympic tales, which are not to be found in the epos; there they are taken for granted as a general mythical background to the main story.

Yours sincerely

Emil