ARS GRATIA ARTIS

|

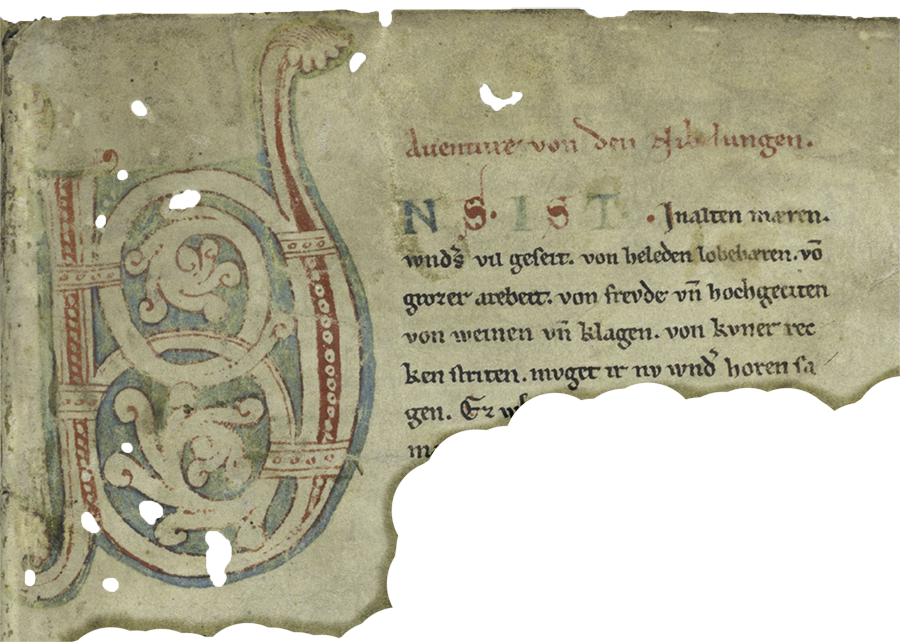

| Introductory Page of Willehalm von Orlens. The author dictating to his scriber Source: Biblioteca Palatina, Heidelberg |

What are we looking at here? Nought other than an epos written by one of the well known authors/poets of the high middle ages! In contrast to his contemporaries, we have no problem locating his work in handwritten parchment. As a well appreciated author, his oeuvres were being copied over and over again, to quench the thirst for high class entertainment at any royal and ducal court in his times.

Nothing gives me greater pleasure than to present to you Rudolf von Ems (about 1195-1254), the noble artist among the Emser. Till now, we only had to deal with warriors, cardinals, popes and saints. But in Rudolf, we encounter real greatness, which has outlasted the ages! Therefore, let's dive into the artist's life and achievements.

He was not a minstrel, which would have been in line with contemporary mores. Rather than travelling from court to court, recitating his work in kind of a sing song to an attentive audience, he was an author in the more modern sense of the world, spreading his art through (handwritten) copies of his oeuvre, to be read by (but of course also recitated to) the literate elite at the noble courts of his time.

Precious little is known about this well published author. Nonetheless, the few facts preserved permit us to make an educated interpolation of his life. His name tells us that he was a younger son or a nephew of an Emser governor of the fortress Ems; as good candidate we have one of the brothers Rudolf and Goswin de Amides, who appear, as Ministerials to the Staufer Henry, Duke of Swabia, in the annals around the 1180s.

|

| A fellow "resident" at the Fortress Ems (William III) Source: Bibliothèke de Genève Boccacio (1410), Des cas des nobles hommes et femmes |

The more observant among my readers may see here an apparent historic discrepancy. Haven't we learned earlier (see Once Upon a Time) that the Emser governors were Ministerials to the Welfer, more precisely to Welf VI, who had the fortress Ems built? But don't you worry! Welf VI's only offspring, Welf VII, died already in 1170, whereupon his father deeded all his possessions to his uncle, Frederic I Barbarossa (1122-1190). That first Staufen Emperor feoffed them in turn to his son Henry, as Duke of Swabia, so as to keep those possessions in the family, rather than under the Crown. And the ministerials followed with the possessions. So there!

Back to Rudolf the author! Given that he must have been born in the Emser domain towards the second half of the 1190s, he would have known, from his early childhood, the prominent captive held in the fortress Ems on behalf of Henry VI (by then elevated to King and Emperor in addition to his title as Duke of Swabia). Let's hope that it did not affect his temperament unduly. As close relative, but not heir, to the governor he may have been destined for a cleric career. In any case, he must have been educated at a solid place of learning, since he proved to be proficient in both Latin and French and rather knowledgable in the arts of his time. We can guess at the Abbey of St Gallen, the location of learning closest to the Emser domain.

Despite being a promising pupil, he was not destined to become a cleric. Already as youngster he produced poetry of a kind that must have irked his cleric teachers. We know this, since he himself mentions those early poems in his later work as "Ich hân dâ her in minen tagen; leider dicke gelogen; und die liute betrogen; mit trügeliche maeren" (I have in my [younger] days put down a lot of lies and fooled people with deceptive worldly tales), which he deplores and wishes forgotten. Thus, he might have become a rather hopeless and destitute member of the Ems dynasty, had not some benefactors discovered his genius and encouraged him to to engage in serious writing.

|

| Shield of Count Hugo I von Montfort Source: Scheibler'sches Wappenbuch |

His first notable book, Der guote Gêrhart (finished around 1220) is not only his first but also, seen with modern eyes, his most accomplished oeuvre by far. It is of innovative design, hitherto not used in contemporary literature, consisting of a tale within a tale as it is. As another first, it contains the story of a commoner. Finally, the "inner tale" (the commoner's story) is told in first-person mode, a method hitherto completely unknown in German literature. As to content, the framing tale describes the character of Emperor Otto the Great, not very flattering, as quite arrogant and lusting for God's praise for his many good deeds. In response, God refers him to a merchant in Cologne, the "guote Gêrhart", so as to learn the story of that man's life. The merchant complies, showing himself as a man of considerable virtue but, foremost, of utmost humility. Thus chastened, the Emperor promises God to amend his ways.

As all the books of Rudolf's time, this work is based on precedents. But, in contrast to most, there was in this case no template, written in a language of Rudolf's knowing, to knead further and imbue with personal traits. There was a story similar to Gêrhart's life in circulation in his times, but it had its origin in North Africa and existed only in Arabic, written by a Jewish scholar (Rabbi Nissim Ben Jacob's book from around year 1000, An Elegant Compilation concerning Relief after Adversity). Most probably, the story came to Europe through Moorish Spain and was retold orally in learned circles.

Rudolf's work received great acclaim upon its appearance, in particular among circles close to the Staufer dynasty. It came out just a few years after the abdication and death of the Welfer "usurper" Emperor Otto IV (1175-1218) and was read by many as criticism of his character, loosely disguised as that of the Saxon Emperor Otto the Great (912-973).

|

| Picture from Barlaam und Josaphat Source: The J Paul Getty Museum |

|

Pages from Alexander

Source: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

|

Von Winterstetten was powerful enough to stay in imperial service despite the King's sudden dethroning, and commissioned Rudolf to start yet another epos, called Willehalm von Orlens. This story, based on French precedents, may have been intended as a means for moral education of Fredric's second son Konrad IV who, albeit crowned King of Germany in 1237, was still only nine years of age. This work came to a successful conclusion, got very famous and well read – to judge from the number of still existing parchment copies – and must have endeared him to the King, who may well have seen Rudolf as some kind of spiritual father figure, in the absence of his real father, who spent most of his years in Sicily.

Konrad IV (1228-1254) had a difficult time in his teens, with not only one but two contender kings challenging his rule. For a time he even had to retreat to his Ducal domains in Swabia as a last hold-out in face of his competitors' armies. To console himself and be inspired to endure, we may surmise, he commissioned Rudolf to embark on his largest production by far, a World History in rhyme, the Weltchronik! The indefatigable poet threw himself into this work and managed, in just a few years in the late 1240s, to carry the story forward all the way to King Solomon the Great.

But again, work came to a standstill when Konrad went to Italy with his army, in 1251, to reaffirm his authority as King of Sicily, after his father's death in 1250. Apparently, Konrad could not be without his spiritual father who, despite his – for the time – advanced age, had to accompany his ruler on that campaign. Alas, both of them came to a sordid end in 1254, dying of camp fever in a base near Naples, together with many a soldier in the royal army.

Let us round up this tale of a remarkable medieval artist by looking at two pages from his unfinished Weltchronik. They deal with Noah and the fresh start the world had to go off to after the Great Deluge. Next time you will hear from me, a corresponding catastrophe would yet affect the path of European history.

|

| Young King Konrad IV |

But again, work came to a standstill when Konrad went to Italy with his army, in 1251, to reaffirm his authority as King of Sicily, after his father's death in 1250. Apparently, Konrad could not be without his spiritual father who, despite his – for the time – advanced age, had to accompany his ruler on that campaign. Alas, both of them came to a sordid end in 1254, dying of camp fever in a base near Naples, together with many a soldier in the royal army.

Let us round up this tale of a remarkable medieval artist by looking at two pages from his unfinished Weltchronik. They deal with Noah and the fresh start the world had to go off to after the Great Deluge. Next time you will hear from me, a corresponding catastrophe would yet affect the path of European history.

|

| Source: Bibliothèque de la ville de Colmar |

Comments

Hadar

How interesting to hear that you also have a writer in the family! Maybe a reminiscence of Rudolf’s good writing has been passed on to you! I am convinced that your excellent way of describing history originates from him.

Kind regards

Eva

You carry on the family gift of fine writing- especially of the historical narrative- most admirably. Rudolf, et alii, would be so proud!

Yours, Per