MAGISTER MILITUM

|

| The Obrister Artist: Erhard Schön Inscription: Hans Sachs Source: Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig |

We are looking here at a Chief Commander of Landsknechte regiments (Oberster Feldthauptman, also called Obrister). He was the backbone of the mercenary war machine in Renaissance times. As prime mover and shaker, his role was to recruit Landsknechte, to organise them and to lead them to battle. But, why not let Hans Sachs, the “Meistersinger”, explain this to us in his own words (in rough translation):

I am the Landsknechte Chief Commander.

I recruit men free of bonds,

muster them and pay them gold.

Then lead them, well equipped with armour,

to war, to meet the enemy.

Fierce attacks I plan for them,

fire them on with words of God,

to do their best on the field of war.

To show my rank above them all,

my pay per month is a hundred doubloons!

It was during the Renaissance wars that Imperial mercenary infantry, the Landsknechte, was honed to perfection. We are not speaking here of small hosts of paid soldiers roving the land. Rather, these were formidable regiments of at least 4000, and at most 12000 men, well trained and led. No wonder that an Obrister, who could assemble, organise and equip such mass troops and, most importantly, lead them to battle, was in sharp demand and highly regarded/rewarded. We shall not forget that the Obrister led the attacks in person, in contrast to modern age generals. Not many of them managed to stay alive for more than a couple of active years. The precious few who survived a longer range of campaigns, stood out and were recognised as true “war heroes”, amassing large fortunes and rising in Imperial rank.

|

| A large Landsknechte regiment at war, adjoined by artillery and light cavalry In Fronsberger (1573), Kriegsbuch, Ander Theil Artist: Jost Amman |

One Emser stands out as one of the most long-surviving and formidable Landsknechte Obrister in early Renaissance. His name was Merk Sittich von Ems zu der Hohenems (ca 1466-1533), from the Hohenems branch of the family. In contrast to his Dornbürner second cousin Jakob II (see Quem Dei Diligunt), he “lived to fight another day” up to his relatively old age of more than 60 years.

His fate was not pre-ordained. His role could have been that of a “Landjunker”, like his father, taking care of the family estates. But this was not to be. His physiognomy dictated another career.

|

| Woodcut in Schrenck von Notzing (1601), Armamentarium Heroicum Artist: Giovanni Battista Fontana Source: British Museum |

Merk Sittich turned out to be a giant of a man, a head taller than any of his Vorarlberg compatriots. His personality was aggressive and dominant. Violent and brutally efficient in leading his troops to attack, but also composed and cooly calculating in withdrawals and defeats. These were precisely the traits asked for by the sovereigns, ever looking for able commanders in their never ending conflicts. His Landsknechte both feared and respected him and, more importantly, were eager to follow him, since his leadership enhanced the probability of them returning home, and with rich spoils to boot.

|

| Learning to use the broadsword In Mair (1540), Opus amplissimum de arte athletica Artist: Jörg Breu the Younger Source: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek |

Little is known about his early years. But we can safely assume that his education was heavy in the martial arts; less so, if at all, in the arts or letters. This in contrast to his partner-in-arms Georg von Frundsberg, who knew to put his words well, in speeches as well as in reports to his sovereign, thereby earning him more visibility in the history of Renaissance conflicts. Merk’s excellence did not reside in words. He spoke through his deeds, and deeds there were aplenty.

He appears in the annals for the first time in 1499, in Maximilian’s Swabian War (see Was He Their Emperor?). As commander of the Landsturm (regional guard) in his home region, he managed to throw back, over the Rhine, a small Eidgenossen army, after killing in single combat both its leaders. This saved the domains close to home from certain destitution. That about the same time as the main army suffered crushing defeat at the two battles of Hard and Frastanz, just a few miles North and South of Hohenems, with wide areas being plundered and devastated as result.

|

| The battles of Hard and of Frastanz in 1499 In Schilling, Diebold (1513), Die Eidgenössische Chronik Source: Zentralbibliothek Luzern |

No wonder Maximilian got his eyes on him. Soon he was taken into the Emperor's service, and entrusted with recruiting, organising and training Landsknechte on the Alpine Rhine. The preconditions were rather favourable. One century and a half had passed since the Great Plague and the population had recovered with a vengeance. Concurrently, the climate had kept on deteriorating, with harvests getting more sparse by the decade.

A surplus of impoverished peasants and burgers jumped at the opportunity to claw themselves out of misery, however risky and deadly the alternative, with rich rewards reaped by only a few lucky survivors. Regiment after regiment was being stamped out of the meagre grounds, so that the region soon got to be known as the “Landsknecht Landel”. Also lower nobility and affluent burgers joined in, manning the lower ranks of command. The main recruting centre, the town of Feldkirch not far from Hohenems, was at the time given the suffix of “Offizier-Städtchen”.

Soon, Merk Sittich was called to service in military campaigns. Here he proved his worth as a foremost commander in battle. During fully thirty years, hardly a season went by without him being engaged in military campaigns. He fought persistently and widely, with war theatres ranging from Apulia in the South to Flanders in the North, from the Champagne in the West to Hungary in the East. It would strain the frame of this story to deal with them all, so we content ourselves with a few telling escapades.

|

| Betrayal at Novara In Schilling Diebold (1513), Die Eidgenössische Chronik Source: Zentralbibliothek Luzern |

Merk Sittich was the first commander leading Landsknechte to battle in the Great Italian Wars, more precisely the second of those wars. Already in the year 1500, Merk Sittich was sent with a small contingent of infantry to the Lombardy, in order to assist Ludovico Sforza (Il Moro), Duke of Milan and Maximilian’s brother-in-law, in his struggles with French King Louis XII. Alas, at Novara in May, Ludovico was taken prisoner, after having been betrayed by his Swiss mercenaries, and Merk Sittich was forced to share his fate, losing the war chest and his private belongings to the enemy.

|

| The Duke de Nemours, French Viceroy of Naples, shot at the Battle of Cerignola Artist: Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz Source: Museo de Prado |

Just one year later, he had already advanced to a major military leader. That year, Ferdinand of Aragon and Frederic of Naples asked King Maximilian for aid, in their efforts to regain the Kingdom of Naples held by the French. Two Landsknechte regiments were formed, commanded, respectively, by Prince Rudolf of Anhalt and Merk Sittich. They sailed to the aid of the Spanish in Apulia, and constituted an important re-enforcement of troops there, led by El Gran Capitan (Gonzalo de Cordoba), which were greatly outnumbered by the French. After two years of cautious manoeuvering, matters came to a crushing conclusion at the Battle of Cerignola (1503), where the French army was annihilated, the French Viceroy felled by a bullet and French reign in Southern Italy put to an end.

After five more years of various campaigns, we find Merk Sittich with a small troop (1700 strong) of Landsknechte assisting Commander Sixten von Trautson in the occupation of the East Dolomite valleys near present day Cortina d’Ampezzo. Early in the year, King Maximilian had sought to transit the Venetian territories on his way to Rome, to be crowned Emperor by the Pope. The Venetians, not trusting the King’s intentions, had refused him categorically. As revenge, the King had opened a single war against Venice, which was successful initially.

But, as so many of Maximilian’s campaigns, this one sizzled out due to lack of funds and hapless planning. In contrast, Venice assembled a sizeable army and its Commander, Condottiere Bartolomeo D'Alviano, began to throw back the Imperial troops. The main battle was at the Canober Valley (Valle di Canove), where Trautson and Merk Sittich were entrenched. Despite the fact that they were seriously outnumbered, the Venetians counting fully 10000 men, Trautson sounded the attack, against Merk Sittich’s firm advice. Most of the Landsknechte were brutally slaughtered in a crafty ambush. Trautson was killed as well as most troops, only a few commanders being taken prisoner, Merk Sittich with them, to be released first after an armistice was agreed upon soon after.

|

| The beautiful Cadober Valley ... ... sight of a brutal slaughter Source: Visitaly Engraver: Giulio Fontana (after a lost print by Titian) Source: British Museum |

This traumatic experience helped Merk Sittich to mature into a fully fledged military leader. His years as apprentice and journeyman of war were gone; thereafter, he was a true Master of Warfare. Never again would he allow himself to be taken prisoner. Never again to be led to certain defeat by reckless or incompetent general command. Never again would he attempt to keep a campaign alive despite dearth of funds and supplies. And, above all, never would he agree to put up Landsknechte troops using his own means, as Georg Frundsberg did to his detriment and sore destitution (see Three Heroes at Pavia). Immense wealth and high status was his reward for consistently holding his destiny in his own hands.

Fast forward seventeen years to 1525, Merk Sittich's year of glory as well as of ignominy. Early in the year, he was instrumental in deciding the arguably greatest and most famous battle of the Renaissance. Whilst the Imperial arrmy was besieging the French King Francis’ army at Pavia, the three regiment commanders, Marquis de Pescara, Georg von Frundsberg and Merk Sittich von Ems essentially forced the two Commanders-in-Chief to go to the attack, following a battle plan conceived by the three, less their mercenaries would leave the field in view of the war chest being scratched to the bottom. Only the prospect of rich booty could hold the army together at that stage. The two Commanders gave in and entrusted Pescara with the general leadership of the attack. The rest is history, to be explained more in detail in another Chapter (see Three Heroes at Pavia).

|

| Gobelin depicting the Battle of Pavia. In the centre, King Francis I, about to be taken prisoner Artist: Bernard van Orley Source: Museum of Capodimonte, Naples |

Whilst the great combat between the Houses of Habsburg and Anjou raged on the battlefields of Europe, the German regions were thoroughly shaken by an internal conflagration. Times were ripe for popular uprising: increase in population combined with worsening economic conditions due to an ever harsher climate weighed heavily on all groups of society.

Whereas nobility and clergy sought to maintain their living standards through ever increasing taxes, peasants and burghers in the towns were squeezed on both sides: by decreasing revenues and increasing levies. Discontent grew among the lower classes and was additionally fomented by religious reformers, such as, Thomas Müntzer and Martin Luther.

|

| A Declaration of Human Rights... first cautiously endorsed by Martin Luther... to be brutally condemned later |

At the outset, in the beginning of 1525, the revolt started peacefully, with large groups of peasants and burgers organising in Swabia and formulating a bill of demands for reform, which was presented to the Swabian League in the form of the “Zwölf Artikel” (twelve articles). The content was radical, it amounted to the first Declaration of Human Rights in Europe, and too far reaching by far for the sovereigns, who tried to disarm the demands by prolonging discussions and delaying responses. To no avail, the revolters armed themselves and went to war against the upper classes. Soon most of Southern and Central Germany went up in flames, in the Great Peasants' War of 1525.

|

| The Weinsberg Massacre Count von Helfenstein (Governor of Württemberg) forced to run the gauntlet Artist: Fritz Neuhaus (1879) Source: Kunstpalast Düsseldorf |

The Emperor made haste to call back his troops form the foreign battlefields. Frundsberg and Merk Sittich both followed the call. Frundsberg joined the main army against the peasants, led by Georg, Truchsess von Waldburg. Merk Sittich, on the other hand, was appointed Commander of a Southern army, consisting of his own Landsknechte, the Landsturm in Vorarlberg (the regional guard) and heavy cavalry from the Swabian League. His task was to quickly quench the revolt North and North East of Lake Constance, lest the war spread into the Alpine Rhine regions South of the Lake.

Merk Sittich gave short thrift to the peasants in Southern Swabia. In two sharp battles, most of their army was defeated. On July 4, a final battle was fought at Hilzingen in the region of Hegau, putting an end to the uprise in the region with unconditional surrender of all remaining peasant hosts. Several hundred commanders were tortured and executed, more than 24 hamlets burned down and all surviving participants of the revolt punished with huge penalties.

A single event in this terrible recriminatory act deserves further notice. Prior to battle, the peasant army located in Hilzingen had lowered a bell from the belfry, to forge it into a cannon. Merk Sittich got hold of it and had 50 of the captured peasant leaders draw it, like oxen, on the loong winding road to the border of Lake Constance. There they were put on a boat together with the bell and shipped across the Lake. Off the boat they went, to be summarily hanged on the oaks adjoining the road to Bregenz. The bell itself was shipped on to Hohenems, where it is adorning the church to this very day. Ever since, the oaks were called the “Henkeichen” (hanging oaks).

This incident did not precisely endear Merk Sittich to the people in Vorarlberg. Ever since, he carried a mark on his name, and was even known in the region by the suffix “Der Bauernschlächter” (slaughterer of peasants). Granted, acts of aggression and violence were not unknown to the Vorarberger. They were living on the border to the ever aggressive Eidgenossen and had been subject to many weaponed incursions from the other side of the Alpine Rhine, with killings, plunder and devastation as result. Many a Landsknecht had also returned from foreign wars, telling stories about his experiences. Had Merk Sittich hanged those poor peasants far away from home, hardly any of his neighbours would have blinked an eye. But the sight of fifty corpses, slowly swinging in the breeze from oaken branches and rotting in the Summer sun, brought the message close to home: a brutal warlord was residing in their midst.

His reputation was further tarnished through his actions as regional administrator. Already in 1513, Merk Sittich was appointed Governor of the Habsburg domains of Bregenz and, soon after, Bludenz-Sonnenberg; all in all, almost two thirds of their domains in Vorarlberg. Since Maximilian I himself was the overlord, in his capacity of Count of Tyrol, and a very absent ruler, and Merk Sittich was his confidant, the Governor ruled supreme over these areas. In addition, Maximilian designated him as Commander of all troups in Vorarlberg, which compounded his influence in the region.

|

| The town of Bregenz In Zeller (1643), Topographia Sueviae Artist: Matthäus Merian |

Maximilian also rewarded him for his services by granting him full sovereignty over the Hohenemser domains, including all judicial rights, rendering him an absolute ruler over his subjects in his own small “kingdom”. In contrast, the residents in the Habsburger domains in Vorarlberg enjoyed considerable co-decision rights, which they had acquired in the century after the Great Plague and, in particular, after the Appenzeller Wars (see On The Edge). Now, as governor, Merk Sittich rode roughshod over these rights and considered his might as governor similar to the power he held at home.

No wonder that the residents in the Habsburger domains reacted. Numerous complaints were lodged against Merk Sittich’s rule, at the regional courts as well as at the Kammergericht in Innsbruck. But to no avail. Court officials were well aware of Merk Sittich’s power and chose wisely to lay all complaints “ad acta”. First after the Governor’s death, in 1533, the “acta” came back to roost and greatly plagued his son and successor Wolf Dietrich von Ems (1507-1538), who did not have the same backing of his Emperor and had to deal with a host of court cases.

Successful as he was in war, immensely wealthy as he was as a result, and as powerful as ruler of Vorarlberg, the tarnish on his name spilled over to and brought problems to his descendants. Precisely when his grandson and great grandson sought to embellish the Emser territory, aiming to raise the family status to that of Imperial Princes, people in Vorarlberg would remember and do their utmost to frustrate those attempts.

-o-

Our sojourn in Renaissance times is coming to an end, after fully six blog chapters. Those were turbulent times indeed, full of extremes, from outstanding grandeur to gruesome violence. With Knights turning into Princes, Princes into Kings and Kings into Emperors. With Kingdoms being created and destroyed at the throw of a dice, an Empire annihilated by a formerly nomadic tribe, and another heavily assaulted by it. With two great powers fighting over global supremacy and only the Pope being able to end the conflict by dividing up the world between the two. With even his Holiness egging on to war the rulers of Europe, in the vainglorious hope that all Italy would fall under celestial rule.

With hosts of peasants and shepherds streaming down from the Alpine valleys to kill off a Prince in the West and defeat even an Emperor in the East, and carve out a small realm for themselves on their mountains and high plateaus. With all the peasants rising in the great Empire and simple monks and preachers fomenting their ire with sermons of religious reform.

With a flood of wisdom streaming Westward from the vanquished Empire in the East and rejuvenating a stale and withering trove of beliefs. With great men of the arts, letters and sciences stepping forth and forever changing our understanding of man’s place in the Universe.

|

| Galileo before the inquisition Painter: Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury (1847) Source: Musée du Luxembourg |

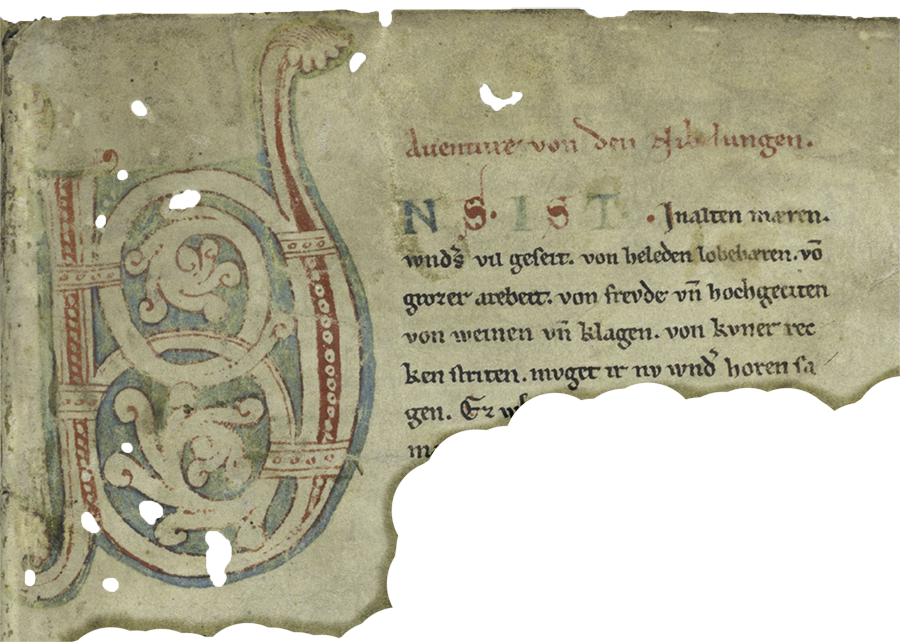

In this great scheme of things, we tried to focus on describing the fate of the House of Ems. To our regret, no great man of the arts, letters or sciences was to be found among them. No likes of a Rudolf von Ems (see Ars Gratia Artis) appeared among the Renaissance Emser, to be worthy of our admiration. Their achievements lay elsewhere. They were outstanding in the art of warfare, true entrepreneurs in mercenary violence.

Their main area of activity lay in the time and theatres of the Great Italian Wars. We are almost tempted to call those the Great Emser Wars, so prevalent was their participation therein. Fully eight Emser fought as Obrister of Landsknechte troops during the 60 years’ lifespan of those wars. To this has to be added a considerable number of illegitimate offspring that fought as captains or simple Landsknechte under their command (e.g. Georg Emser, who fell with Jakob II in Ravenna, see Quem Dei Diligunt). These eminent fighters served under a sizeable number of sovereigns: two Dukes, six Kings, three Emperors and one Pope.

Permit me to round up these conclusions by presenting three generations of outstanding Renaissance Masters of Warfare, consisting of Merk Sittich von Ems zu der Hohenems, his son and his grandson. They were living in an age of tremendous conflicts and grasped the opportunities offered therein. In modern day words, they were true entrepreneurs of mercenary enterprise. In another time, their excellence might have led them to become magnates of industry, a Carnegie or Ford alike, or why not a Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk or Richard Branson. And, indeed, they were magnates of one of the foremost industries of their time, and exploited its opportunities to the utmost. As a result, the House of Ems rose from a small Knighthood on a diminutive domain to immense riches and high Imperial nobility.

Would it last? Or would the laws of nature re-establish themselves, forcing down succeeding generations to the mean? Or even worse? Patience, Dear Readers! The answer to these questions will have to await the coming chapters of this blog.

Comments

Cheers, Franklin