THE KING IS DEAD, LONG LIVE THE ...?

|

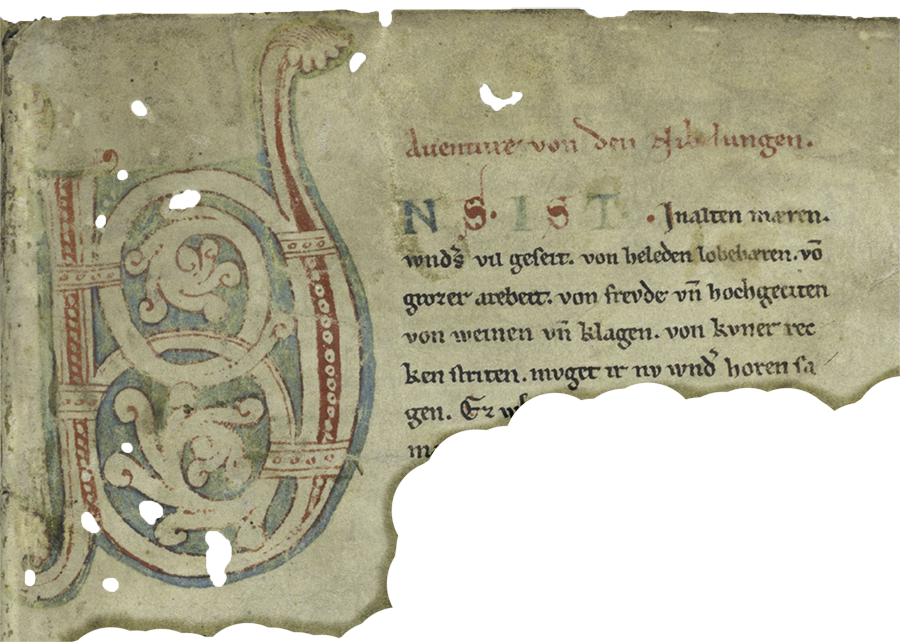

| Heinrich Knoblochtzer (1488), Heidelberger Totentanz Source: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg |

This somber page from a book published a century after the fact reminds us of the greatest catastrophe experienced by civilisation within the last millennium and a half. In the mid-1300s the world came to an end, or so contemporaries believed. Black Death ravaged through Eurasia, mowing down its populations by the millions. Not since the mid-500s had anything like it been experienced, neither after the 1300s.

Compared to this cataclysm, the Great War and WWII, even counted together, almost seem like a minor skirmish. The number of dead was staggering, rising up to 200 million all over Eurasia. In absolute terms this is at par with the count of victims of the two World Wars, but the overall population in those days was many times smaller! All in all, up to 50% died in Europe alone within just a few years. Nobody was spared, rich or poor, young or old, all were mowed down without mercy by the Reaper's scythe.

The world did not come to an end; but, the middle ages did, even if it took another century for the repercussions to work themselves through all segments of society. Civilisation did not break down, as it would in present days with a similar death toll; self-sufficiency was still prevalent in the mostly rural communities. But the fabric of society weakened and sometimes broke, putting an end to the slow and steady progress of communities, regions and states, hitherto well-ordered under the stationary system of feudalism.

How did the Emser fare in these difficult times? We sorely lack documentation about how the family was directly affected by the Plague, besides the obvious, that it did not die out completely. There is ample documentation, but it refers mainly to land sales and acquisitions, acting as witness to other people's corresponding affairs, and to the family's relations with their overlords during the period. So, let's do our best and reconstruct the Emser destiny throughout two centuries; first, in this blog, the period leading up to the cataclysm and then, in the following blog, the much more laborious, albeit more dynamic years thereafter.

A good starting point is where we left off in the preceding blog post (Ars Gratia Artis). You may recall that Rudolf von Ems the "family poet" died in Southern Italy in 1254, as did young King Konrad II. With the latter, the Staufen dynasty evaporated and thus, the last strong royal dynasty in Germany elapsed, leaving a power vacuum that would last fully twenty years. The period is called the Great Interregnum.

In this period, there was effectively no royal rule in Germany. There were kings reigning, most of the time two competing ones, but they did not have any power. Some of them did not even bother to travel to Germany to be enthroned; it simply was not worth the effort. The power to rule had been devolved down to the grandees of Germany, the great noble dynasties that reigned over large swathes of the country, each acting like a small king in his territory (one of them actually was a king, the King of Bohemia). There were seven of them, and only these Prince-Electors had the right to appoint the King. So they saw to it that no powerful ruler be chosen, lest they lose their own right to rule.

In territories like Swabia, where there was no grandee ruling any longer (the Staufen had been Duke of Swabia as well as King/ Emperor), the peace of the land, upheld by the ruler, was gone. Similarly in the North of Germany. Smaller noble domains, royal cities and regions held by free peasants realised that they were without protection and started to organise defensive leagues that may eventually become ruled regions of their own. Examples of this can be found in the Hanseatic League to the North, the City Leagues in Swabia and elsewhere and, last but not least, the Eidgenossenschaft between the high valleys South of the St Gotthard Pass, the embryo of present day Switzerland.

On the Alpine Rhine, the counts that had lost their overlord (the Stauffen Duke of Swabia), took matters in their own hands; not only that, they made haste to enlarge their territories by grabbing the ducal domains close by. Thus the reign and power of three comital dynasties was greatly enhanced: that of the Montforter (right side of Lower Alpine Rhine), Werdenberger (left side of Lower Alpine Rhine) and Habsburger (West of the Alpine Rhine).

How did this affect the Emser? The fortification of Hohenems, as a Staufen Ducal Domain goverrned by the Emser Ministerials, lay smack in the middle of the large Montfort domains, just like the other Staufen fortifications along the Rhine that guarded the road to Italy. Not surprisingly, Hohenems was soon incorporated into the Montfort comital domains, albeit still being governed by the Emser as Ministerial. The latter had nothing to lose by subjecting themselves to the Montfort Count, since they held no hereditary rights to the fortification.

Had the Emser remained as officials of the Montforter, they would certainly have faded away as notable figures in history, sharing the fate of their Lords, who left the scene just a hundred years later (with the Habsburger stepping in to reign over most of the right side Lower Alpine Rhine).

Fortunately, a strong and crafty figure stepped into the foreground, who would rock the boat of the power hungry counts on the Alpine Rhine. This was Count Rudolf von Habsburg (1218-1291), one of the three "land-grabbers" in the area. In 1273, just when Rudolf was about to besiege the town of Basle, in yet another attempt to grab a Royal lien, a courier reached him with the welcome news that he was to be elected King of Germany. Thus, one of the playing mice became the cat!

|

| Baseler Totentanz Source: Historisches Museum, Basel |

How did the Emser fare in these difficult times? We sorely lack documentation about how the family was directly affected by the Plague, besides the obvious, that it did not die out completely. There is ample documentation, but it refers mainly to land sales and acquisitions, acting as witness to other people's corresponding affairs, and to the family's relations with their overlords during the period. So, let's do our best and reconstruct the Emser destiny throughout two centuries; first, in this blog, the period leading up to the cataclysm and then, in the following blog, the much more laborious, albeit more dynamic years thereafter.

A good starting point is where we left off in the preceding blog post (Ars Gratia Artis). You may recall that Rudolf von Ems the "family poet" died in Southern Italy in 1254, as did young King Konrad II. With the latter, the Staufen dynasty evaporated and thus, the last strong royal dynasty in Germany elapsed, leaving a power vacuum that would last fully twenty years. The period is called the Great Interregnum.

|

| Also das Römische Rich eine Wile one Keiser stunt (Thus, the Roman Empire was without Emperor for a time) Martinus Oppaviensis (1450), Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum |

In this period, there was effectively no royal rule in Germany. There were kings reigning, most of the time two competing ones, but they did not have any power. Some of them did not even bother to travel to Germany to be enthroned; it simply was not worth the effort. The power to rule had been devolved down to the grandees of Germany, the great noble dynasties that reigned over large swathes of the country, each acting like a small king in his territory (one of them actually was a king, the King of Bohemia). There were seven of them, and only these Prince-Electors had the right to appoint the King. So they saw to it that no powerful ruler be chosen, lest they lose their own right to rule.

In territories like Swabia, where there was no grandee ruling any longer (the Staufen had been Duke of Swabia as well as King/ Emperor), the peace of the land, upheld by the ruler, was gone. Similarly in the North of Germany. Smaller noble domains, royal cities and regions held by free peasants realised that they were without protection and started to organise defensive leagues that may eventually become ruled regions of their own. Examples of this can be found in the Hanseatic League to the North, the City Leagues in Swabia and elsewhere and, last but not least, the Eidgenossenschaft between the high valleys South of the St Gotthard Pass, the embryo of present day Switzerland.

|

| The Seven Prince-Electors Codex Balduini Treverorum (1341) Source: Landeshauptarchiv Koblenz |

On the Alpine Rhine, the counts that had lost their overlord (the Stauffen Duke of Swabia), took matters in their own hands; not only that, they made haste to enlarge their territories by grabbing the ducal domains close by. Thus the reign and power of three comital dynasties was greatly enhanced: that of the Montforter (right side of Lower Alpine Rhine), Werdenberger (left side of Lower Alpine Rhine) and Habsburger (West of the Alpine Rhine).

How did this affect the Emser? The fortification of Hohenems, as a Staufen Ducal Domain goverrned by the Emser Ministerials, lay smack in the middle of the large Montfort domains, just like the other Staufen fortifications along the Rhine that guarded the road to Italy. Not surprisingly, Hohenems was soon incorporated into the Montfort comital domains, albeit still being governed by the Emser as Ministerial. The latter had nothing to lose by subjecting themselves to the Montfort Count, since they held no hereditary rights to the fortification.

Had the Emser remained as officials of the Montforter, they would certainly have faded away as notable figures in history, sharing the fate of their Lords, who left the scene just a hundred years later (with the Habsburger stepping in to reign over most of the right side Lower Alpine Rhine).

Fortunately, a strong and crafty figure stepped into the foreground, who would rock the boat of the power hungry counts on the Alpine Rhine. This was Count Rudolf von Habsburg (1218-1291), one of the three "land-grabbers" in the area. In 1273, just when Rudolf was about to besiege the town of Basle, in yet another attempt to grab a Royal lien, a courier reached him with the welcome news that he was to be elected King of Germany. Thus, one of the playing mice became the cat!

|

| Rudolf besieging Basle Schilling (1485), Spiezer Chronik Source: Burgerbibliothek Bern |

Rudolf wasted no time to fill the power vaccum that had reigned during the Interregnum. He convinced the Electors of the need to reinstall royal control of regal domains, with the tacit proviso that they could themselves enact this restitution in their domains at their leisure. In only two regions did he insist on leading the act of restitution, the Southeast and Southwest of Germany.

In the East, Přemisl Ottakar II, the King of Bohemia, had "appropriated" the Duchies of Austria, Styria and Carinthia, as well as the March of Cariola (most of present day Austria and Slovenia). After several years of conflict, Rudolf prevailed in the Battle of the Marchfeld and gained control of these domains. Eventually, he invested his son Albrecht with the Duchies of Austria and Styria, thus elevating the Habsburger to princely status.

In the West, the master plan was to regain all the crown possessions in Swabia and use them as base for reinstalling the Duchy of Swabia, with his son Rudolf as Duke and possible successor to the Crown. Somewhat prematurely, he already gave the ducal title to his son and proceeded by clawing back the lost domains, with armed forces wherever necessary. The Montforter were among the most affected and lost again all their recently grabbed possessions, including the fortress of Hohenems as one of the former Staufen fortifications along the Rhine. Thus, the Emser, originally being Ducal Ministerials, became, via Comital Ministerials, finally Royal Ministerials, governing Hohenems on behalf of the Crown! And this position they kept, since King Rudolf never could implement fully his master plan, with his son Rudolf dying before him and the Electors vehemently refusing to either restoring the Duchy of Swabia or crowning his other son Albrecht as successor King.

The following king, Adolf of Nassau, and his successors Albrecht I and Henrik VII of Luxemburg, had scant interest in the Alpine Rhine region, occupied as they were with gaining and maintaining their reign in the heartlands of Germany. The Imperial ambition to reign over the whole of Italy had died with the Staufen Emperors and thus the need to fortify the roads South to and over the Alps was of less concern to their successors. This left the Emser on their fortification pretty much to their own devices. Gradually, they started to think about themselves less as Ministeral to the King and more as independent holder of the fortification and its surrounding lands.

Things became more precarious when Henrik VII died in 1313, only five years after his coronation. The Electors, in their wisdom, elected, in 1314, two successors simultaneously, the Wittelsbacher Louis IV the Bavarian (1282-1347) and the Habsburger Frederick the Fair (1289-1330). Now, good advice was dear: whose side to choose as overlord? The Emser were lucky, in choosing the Wittelsbacher, whose Ducal territories were closer to their own. The fight between the two competitor kings went undecided for almost ten years, until the battle of Mühlheim (1322), when Lous finally go the overhand.

Soon after the battle, Louis was crowned Emperor. Subsequently, he thanked the Emser for their loyalty by officially investing them, in 1333, with their domain as Royal Lien, also conferring upon them the rank of Knight of the Realm, with only the King/Emperor as overlord. In addition, Louis was prepared to convey (Imperial) city rights, the same as already granted to Lindau, to their settlement below the fortification, provided that a wall be built around the area. The Emser never built such a wall, possibly for being afraid of losing control over the settlement; as city, it were to be governed by an independent council, according to the city rights of Lindau.

Ulrich I von Ems (1287-1357) was the first Emser to carry the title of Knight. It turned out that he had achieved this legally certified position, including the inheritable rights to his domain, just in time. Only som twenty years later, the Great Plague devastated the Alpine Rhine region. Ulrich was the eldest of five brothers. Of them, three died in the decade of the Great Plague, including Ulrich himself. However, Ulrich had five sons (and one daughter), three of whom survived. So the future of the new territorial lords was secured, despite most of their first generation having perished! Even so, prospects looked far bleaker than in past centuries. Fimbul climate started to sneak up on Europe and aggravate living conditions on lands already bereft of half their population. The Little Ice Age was advancing and would affect the Alpine Regions for another four centuries.

Let us round up this dramatic blog post by paying tribute to the innumerable victims having died in the 1350s, long gone witnesses to the ultimate superiority of Nature over Mankind.

In the East, Přemisl Ottakar II, the King of Bohemia, had "appropriated" the Duchies of Austria, Styria and Carinthia, as well as the March of Cariola (most of present day Austria and Slovenia). After several years of conflict, Rudolf prevailed in the Battle of the Marchfeld and gained control of these domains. Eventually, he invested his son Albrecht with the Duchies of Austria and Styria, thus elevating the Habsburger to princely status.

In the West, the master plan was to regain all the crown possessions in Swabia and use them as base for reinstalling the Duchy of Swabia, with his son Rudolf as Duke and possible successor to the Crown. Somewhat prematurely, he already gave the ducal title to his son and proceeded by clawing back the lost domains, with armed forces wherever necessary. The Montforter were among the most affected and lost again all their recently grabbed possessions, including the fortress of Hohenems as one of the former Staufen fortifications along the Rhine. Thus, the Emser, originally being Ducal Ministerials, became, via Comital Ministerials, finally Royal Ministerials, governing Hohenems on behalf of the Crown! And this position they kept, since King Rudolf never could implement fully his master plan, with his son Rudolf dying before him and the Electors vehemently refusing to either restoring the Duchy of Swabia or crowning his other son Albrecht as successor King.

The following king, Adolf of Nassau, and his successors Albrecht I and Henrik VII of Luxemburg, had scant interest in the Alpine Rhine region, occupied as they were with gaining and maintaining their reign in the heartlands of Germany. The Imperial ambition to reign over the whole of Italy had died with the Staufen Emperors and thus the need to fortify the roads South to and over the Alps was of less concern to their successors. This left the Emser on their fortification pretty much to their own devices. Gradually, they started to think about themselves less as Ministeral to the King and more as independent holder of the fortification and its surrounding lands.

Things became more precarious when Henrik VII died in 1313, only five years after his coronation. The Electors, in their wisdom, elected, in 1314, two successors simultaneously, the Wittelsbacher Louis IV the Bavarian (1282-1347) and the Habsburger Frederick the Fair (1289-1330). Now, good advice was dear: whose side to choose as overlord? The Emser were lucky, in choosing the Wittelsbacher, whose Ducal territories were closer to their own. The fight between the two competitor kings went undecided for almost ten years, until the battle of Mühlheim (1322), when Lous finally go the overhand.

|

| Allegedly the Battle of Mühlheim Eschenbach (ca 1220), Willehalm Illustration from a script from 1334 Source: Universitätsbibliothek Kassel |

Soon after the battle, Louis was crowned Emperor. Subsequently, he thanked the Emser for their loyalty by officially investing them, in 1333, with their domain as Royal Lien, also conferring upon them the rank of Knight of the Realm, with only the King/Emperor as overlord. In addition, Louis was prepared to convey (Imperial) city rights, the same as already granted to Lindau, to their settlement below the fortification, provided that a wall be built around the area. The Emser never built such a wall, possibly for being afraid of losing control over the settlement; as city, it were to be governed by an independent council, according to the city rights of Lindau.

Ulrich I von Ems (1287-1357) was the first Emser to carry the title of Knight. It turned out that he had achieved this legally certified position, including the inheritable rights to his domain, just in time. Only som twenty years later, the Great Plague devastated the Alpine Rhine region. Ulrich was the eldest of five brothers. Of them, three died in the decade of the Great Plague, including Ulrich himself. However, Ulrich had five sons (and one daughter), three of whom survived. So the future of the new territorial lords was secured, despite most of their first generation having perished! Even so, prospects looked far bleaker than in past centuries. Fimbul climate started to sneak up on Europe and aggravate living conditions on lands already bereft of half their population. The Little Ice Age was advancing and would affect the Alpine Regions for another four centuries.

Let us round up this dramatic blog post by paying tribute to the innumerable victims having died in the 1350s, long gone witnesses to the ultimate superiority of Nature over Mankind.

Comments

You really do have a masterful way of building in dramatic tension to your posts. Just incredible drama to spark the dense details into life. Very Richard Attenborough-ish!!

I also love the fine illustrations. Yet another great chapter.

Wow, you are SUCH a researcher. And then you put together your facts and figures in a way that is a pleasure to

to read. I always feel a little more educated after finishing one of your treatises. Vielen Dank. Mille grazie.

Dėkui, dėkui -auf Litauisch. Kathy and I are loyal members of your Berkeley fan club. Keep up the good work.

Danutė on Dana Street

The black death is indeed something which we should recall as a catastrophy for Europe. You have done well to remind us of it in such a dramatic way.

All the best

Per

Just to let you know how much I enjoyed your Sept 8 blog post. It made for very enticing reading and I learned quite a lot. I took the liberty of sharing it with a German friend who is like a sister to me. I met her in 1967 when I spent a couple of years at OECD. How time flies!

In the mist of the Chaos in USA, it was a real treat reading your blog. I trust that all is well with you and that you are now fully embracing the fall season.

Thanks again and best regards,

Monique