GREAT EXPECTATIONS

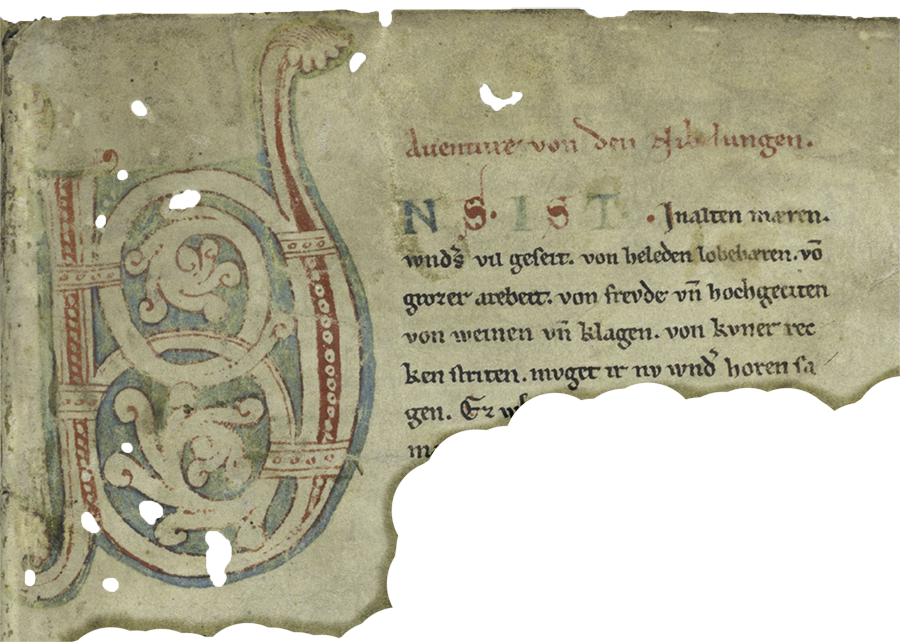

We are looking here at a delicate specimen for bibliophiles. None other than the title and frontispice of the first book ever printed in Vorarlberg and, indeed, in all of the Alpine Rhine region. It is commonly known under the name of “Emser Chronik” and was produced by Bartholome Schnell, the bookprinter who had been brought to Hohenems by Count Kaspar (Der Landesherr). This beauty of a book was the first oeuvre produced by Schnell, right after he had established his printshop in Hohenems in 1616. It can be safely presumed that the Count’s main goal with inviting the printer to Hohenems was to promulgate the noble stature of his House in a worthy publication.

In fact, Kaspar had initiated work on this book already before 1613, concurrent with his negotiations to acquire the domains of Vaduz and Schellenberg. He had engaged his scribe (secretary) Johann Georg Schleh with the task to put his thoughts on paper, including carrying out the necessary basic research with the help of the archives on the Emser premises. There is no doubt that the whole venture was inspired by the Count's ambitions and vision of a Principality of the Lower Alpine Rhine, in the book called "Under Rhetia" (Lower Rhaetia), with the Emser as noble Rulers of it all.

He was crafty enough not to lay open this ambition of his. Instead, the book contains a throrough geographic and historical overview of the region, together with a catalogue of all the noble houses that had ruled all or part of it throughout the ages. Almost by happenstance, the domain of Hohenems, placed in the book’s center, is described in the greatest detail, as is the House of Ems. As further embellishment, the Emser are described as enjoying an ages long noble lineage, with their roots in ancient Etruscia, from where the first of them, like a latter day Aeneas, allegedly moved to the Alpine Rhine region more than 2000 years afore. Thereafter, an impressive array of descendents is catalogued (all mythical) until 1195, from which date onward we meet well documented Emser.

Without it being spelled out, a contemporary reader could not but conclude that Lower Rhaetia was a well defined and homogeneous region, destined to be reigned by the noble Emser. Was it not true that the only noble House still ruling there since the days of yore was the House of Ems?

The Count (together with his brother Merk Sittich IV) then got busy to make this grand vision reality. To succeed, it would need the benevolence and approval of the Imperial House, that is, the Habsburger. There was hope there, they thought, given the centuries' old bond between the two Houses.

As a first foray, the brothers had already in 1611 provided good service to their Imperial Rulers. In that year, Matthias, then King of Bohemia, was wedding his cousin Anna, daughter of the deceased Archduke Ferdinand II (Count of Tirol). Maximilian III, Ferdinand’s successor and Matthias’ brother were to escort the bride from Tirol to Vienna. Unfortunately, he had fallen out with his elder brother, Emperor Rudolf II, and was banned from the capital. Count Kaspar to the rescue. He offered his services as the betrothed’s Cavalier d’Honneur on her voyage to Vienna, thus helping resolve a delicate brotherly dilemma, and gaining the favour of King Matthias.

|

| Three brethren and one betrothed Archduke Maximilian III Emperor Rudolf II King Matthias Anna von Tirol |

The next occasion to approach His Majesty came in March 1613. Just a few months earlier, Matthias had finally been crowned Emperor, after almost a decade’s struggle to dethrone his ailing brother Rudolf. He wasted no time to convene the Reichstag (Imperial Diet), in an attempt to manifest his Imperial status and establish lasting peace and order within his Realm. Was it not being threatened again by re-emerging religious troubles? Protestant and Catholic princes had since some years back intensified their mutual antagonism and even organised themselves in alliances, the Protestant Union and the Catholic League. It was Matthias' aim to ease the tensions and re-affirm the compromise and fragile religious peace reached at Augsburg some fifty years earlier.

About the time of Matthias’ coronation, Merk Sittich IV von Hohenems had embellished his own nobility by getting elected to Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, Primas among catholic cleric princes in the Empire. As one of the Imperial Peers, he of course attended the Diet and Kaspar chose to accompany him. Kaspar had high hopes that Merk Sittich’s elevated position would rub off on him and enable him to further his own plans towards becoming a Prince. Whereas the Count went along with a modest company of some 10 attendees and servants, the Prince spared no expenses to exhibit his newly won grandeur. His escort consisted of more than 400 court officials, hangers on, servants and soldiers, as a way to show off the exquisite position he now occupied within the Empire. As an aside, the Emperor was accompanied by an entourage counting thousands.

|

| Solemn opening of a Reichstag in Regensburg (this one of 1640) Copper engraving in Matthäus Merian (1645), Theatrum Europaeum Source: Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel |

Count Kaspar’s intention was to discretely remind Matthias of having helped him in his marriage execution and thus rekindle his benevolence. At the same time, he hoped that Merk Sittich would put his new elevated position to good use, nudging the Emperor to elevate the House of Ems to Principal status, in view of his own high position and his blood relation to the House. The first part was met with success: the Emperor bid him a cordial (albeit non-committal) welcome. Unfortunately, Merk Sittich did not deliver.

The Prince Archbishop was in delicate quandary. His predecessor, cousin Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau, had just the preceding year been deposed through the intervention of Duke Maximilian of Bavaria; a major cause for this drastic act being Wolf Dietrich’s refusal to commit his Principality to the Catholic League. Thus, Merk Sittich had been elevated to Archbishop only with the proviso, that Salzburg become a Member of the League at long last. Although he had no intention of following through his pledge, he could not openly renege on it just a few months after his inauguration. On the other hand, would he put forward a suggestion to elevate his House, this would inevitably result in a counter-request, by the Emperor as well as the Pope and Duke of Bavaria, for timely accession to the League as part of the deal. So, wisely, he put the welfare of his territory before that of his House and remained silent on the issue of promotion.

Kaspar, disgruntled with his brother's betrayal and disgusted with the display of empty splendour at the “great” event, chose to return home just after a few weeks’ stay. In contrast, his brother remained to bath in his newly attained princely grandeur. In the mean-time, the Reichstag tithered on in a hapless fashion. The Protestant Princes had chosen to be absent, being represented only by minor ministerials. Through them, they insisted that the age-long principle of majority voting be abolished and only decision by consensus permitted. As result, few decisions were taken at the Reichstag, and most of them unimpressive, aside from providing funding for campaigns against the Osmans. In the Reichsabschied (protocol), the list of agreements reached filled out fewer pages than the list of attendants!

From then on, Kaspar was left to his own devices, as concerns promotion activities. The next opportunity to shine presented itself two years later, when political unrest threatened the uneasy peace and stability reigning on the Alpine Rhine. It had its origins in an unusual state creation in Upper Rhaetia, called Graubünden (the Grey Alliances). This statelet, located within the Empire but semi-independent of it, had emerged in the period of unrest and troubles after the Great Plague.

As of old, three overlords dominated Upper Rhaetia, the Prince Bishop of Chur, the Count of Toggenburg and the Count of Werdenberg Sargans. The grip of those sovereigns loosened after the Great Plague, which caused a drastic shift of governance power throughout the following century. It started with the Prince Bishop about to hand over his lands to the (then already Habsburg) Count of Tyrol in 1367. His subjects revolted and formed an alliance of self-governed court regions called Gotteshausbund (Alliance of the House of God; G on the map) effectively emasculating the Bishop’s governance and preventing the Habsburg takeover.

Thereupon followed an alliance of Western court regions called Oberer Bund (Upper Alliance; O on the map) upon the initiative of the Abbey of Disentis, during 1395-1424. Finally, after the death of Frederic II of Toggenburg in 1436 (see Phoenix Ascendens), the Northern court regions formed their own alliance, the Zehngerichtebund (Alliance of the Ten Courts; Z on the map), to prevent any successor lord from assuming power over them.

In 1613, Count Kaspar had acquired the domains Vaduz and Schellenberg (present day Liechtenstein) and thereby become immediate neighbour to the Three Alliances (see Der Landesherr). This was far from a safe and secure position to hold! Rather, he got close to a witches’ brew of conflicts that had brewed for a century and would continue to do so throughout his rule. The Three Alliances, finally having come together to form a loose Union called Graubünden (The Grey alliances) in 1523, a Free State semi-independent of the Empire, found themselves in a situation of never ending troubles, both within their borders and with their neighbours to the East and South.

|

| Foundation of the Oberer Bund (Upper Alliance) in 1424 Borderstone between Vaduz and Graubünden Artist: Fridolin Eggert (1700) Source: Cuort Ligia Grischa Source: Historisches Lexikon des FL |

The Union’s geographic location was delicate. The Bündner controlled major passes between the Empire and the Italian states to the South, in particular the Duchy of Milan, held by Spain, as well as to the Republic of Venice to the Southeast. Whereas the Spanish Habsburger were in alliance with the Austrian Habsburger (and thus the Empire), Venice was their common enemy. France was an additional player in the region, with its own interest to harass trade and movement of troupes between Spanish Milan and the Empire. Finally, the Eidgenossen, bordering the Free State's Western flank, were always ready to interfere and assist their neighbour in times of need. All these foreign powers were permanently trying to get parts or all of the Free State into an alliance to prevent their adversaries from access to the passes.

As recently as 1610, the French were about to start a war with the Empire, prevented only by the assassination of Henry IV of France. Thereafter, the Habsburger took care to bind the Bündner to themselves. But it did not take long for the Venetians to re-enter the fray; in 1615, a war with the Habsburger was imminent in the Adriatic, and Venetian diplomats were busy in trying to get the Bündner into an alliance, together with Zürich and Bern from the Eidgenossen. Concurrently, the Habsburg local governor of some eight court districts owned, within the Zehngerichtebund, by the Count of Tyrol (acquired by Duke Siegmund in 1470) had resigned; it was urgent to find a replacement for this delicate post, lest those domains, mostly protestant and leaning towards the Venetian cause, shake off the Habsburger ownership for good.

Thus the Habsburger had urgent need for a suitable emissary, who could placate the Bündner, convince them to denounce any promises to the Venetians and get them to accept a suitable candidate for the governance of the Habsburg domains in the Zehngerichtebund. Kaspar appeared the given man for the post. Since he was Governor of the County of Feldkirch, he could act as emissary for the Count of Tirol. As Imperial Count of Hohenems, he was a high Lord answering only to the Emperor and could act as emissary for Emperor Mathias. Finally, as Count of Vaduz and Lord of Schellenberg, he was a good and immediate neighbour to the Bündner, and had already declared neutrality for those domains in any conflict between the Bündner and the Habsburger.

|

| The town of Chur, seat of the Bündner Bundstag (Diet) in 1615 Copper engraving in Matthäus Merian (1654), Topographia Helvetiae, Rhaetia, et Valesiae Source: ETH Bibliothek Zürich |

Kaspar travelled to Chur in June 1615. The Graubündner Bundstag (Diet) was in session there and deliberating the Alliances’ relations to Venice. The emissary proved to be a very successful negotiator on behalf of the Emperor and the Count of Tirol. By alternately flattering, threatening and fraternising with the delegates, in addition to presenting an elegant speech at the Diet, he eventually managed to outmanoeuvre the Venetian Ambassador and wean the Bündner off from cooperating with Venice. Soon after this, a suitable candidate for the governance of the eight court regions owned by Habsburg was found, acceptable to the Habsburger and Bündner both; all in all, a remarkable success for Kaspar as Imperial and Comital Emissary.

Finally, in 1620, it was time for the decisive move to promote the Emser to Imperial Prince and sovereign of a sizeable Principality. For a decade already, Count Kaspar had proven himself to be a faithful, efficient and trustworthy ally of the Habsburger. This in a period of relative peace reigning in the Empire. Now, towards the end of the decade, storm clouds were assembling on the North Eastern horizon of Habsburg rule. The Bohemians threatened to dethrone them as their King, and this uprise soon took the form of weaponed conflict. As always, war puts great demands on sovereigns’ coffers. The Count was well aware of this, as Governor of the Habsburg County of Feldkirch. Again and again, demands came to the County for funds to get ever more regiments to fight in Bohemia.

|

| Der Prager Fenstersturz (Defenestration in Prague) in 1618 It sparked a thirty years’ firebrand, devouring the Empire Copper engraving in Matthäus Merian (1646), Theatrum Europaeum Source: BPK |

As Imperial sovereign in Hohenems, Lustenau, Vaduz and Schellenberg, he was not affected by these demands for extraordinary levy. So, he could put conditions on granting any financial support to the war effort from his own domains; a great opportunity to further his cause! In May 1620, he put things in motion with an offer that the Habsburger could, in his view, not refuse. He promised them the princely sum of 100 000 Gulden. In return he asked that the Habsburger cease to him some territory bordering on the Alpine Rhine, so that his domains could stretch from Lake Constance down to the Lucier Steig. Thereby, he would become sovereign of a small contiguous “Principality of Lower Rhaetia”.

Would this principality encompass fully the region of “Under Rhetia”, as outlined in the “Emser Chronik”? Not really; just about a quarter of it. The areas left of the lower Alpine Rhine were already firmly ensconced within the Eidgenossen and unobtainable. Asking for all the large territories outlined to the right of the river would aggravate the estates in those areas, among them the town of Feldkirch, and in any case request an even more princely sum than the offered 100 000 Gulden. That amount was about at par with what Kaspar hoped to receive for selling his County of Gallara near Milan; in 1620, he had no additional funds to put forward any longer.

|

| Count Kaspar’s Masterplan: an offer to replenish the Habsburg coffers – with strings attached |

This new principality, as it was conceived, would act as a neutral buffer state between the Habsburger and the Eidgenossen, as well as the Bündner to the South. Thereby it would, as Count Kaspar figured, be instrumental in keeping peace on the Alpine Rhine, at a time when the Count of Tirol and the Emperor were kept busy to resolve conflicts in the North and North East of their domains. Would Kaspar’s grand vision turn to flesh, at long last? Would the realm thus created deflect the threat of war in the region, at a time of great European conflicts? Would it polish the House of Ems to Princely shine; not through feats of war, but through being a good neighbour and rendering service as Honest Peace Broker? Let’s return to this topic and provide answers in a forthcoming blog post. This one is already filled to the brim with content and we would not dare overuse your patience, Dear Readers.

Comments

Heinz

Heather