DER LANDESHERR

|

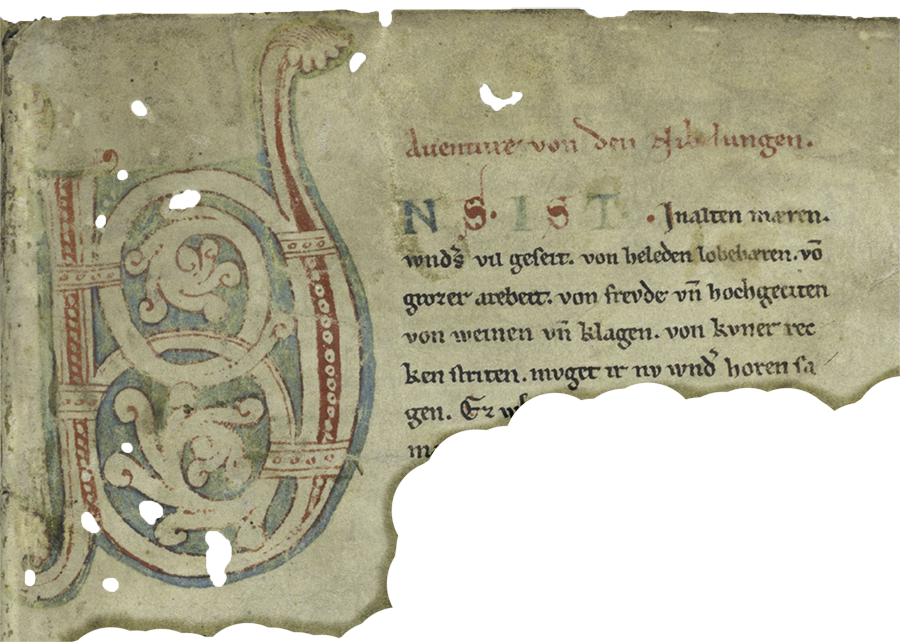

| An Imperial Count with his spouse Excerpts from painting by unknown artist Source: Palace of Hohenems |

The title of this post, Landesherr, can hardly be expressed in English. We come close by translating it as “sovereign of his territory”, but this does not convey its full meaning. In Kingdoms like England and France of the Baroque times, there was only one sovereign, that is, the King. Not so in the (then) only Empire in Christianity, Sacrum Imperium Romanum, the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. This Empire was not a coherent state, like the above mentioned Kingdoms. Rather, it was a loose collegium of semi-independent territories, with an Emperor as figurehead, not unlike the European Union of present times, but more loosely knit together than even that modern conglomerate of semi-independent States.

A professor in jurisprudence, Johann Jacob Moser, put it succinctly, when he stated the following: “Teutschland wird auf teutsch regiert, und zwar so, dass sich kein Schulwort oder wenige Worte, oder die Regierungsart anderer Staaten dazu schicken, unsere Regierungsart begreiflich zu machen”, in Teutsches Staatsrecht (1737) (Germany is governed in the German manner, in a way that no learned concept or concepts, nor the analogy of other States’ reign can help to grasp its manner of governance).

To put it bluntly, within the Empire, there existed, in Baroque times, around 300 semi-independent territories, each governed by its own Landesherr. Most of these sovereigns reigned supreme over their subjects and had full judiciary power over them, except the Lords of the smallest territories, who had to forego the issuing of high criminal justice (implying torture and death sentence). All but the Lords of the lowest rank had a say in the affairs of the Empire, mainly concerning (very limited) taxation, declaring war and peace and putting up men and resources for the Imperial army contingents.

Even if many of these sovereigns reigned over pitifully small domains, being a Lord in the Empire implied the highest status a Lord in Christianity could obtain. Was not the Empire the successor body of Rome itself, headed by an Emperor residing, as King of Kings, far above simple sovereigns such as Kings and Princes? And did not sovereignty over a territory, however small, granted by the Emperor himself, and thus beging blessed with Imperial Immediacy, raise the owner to the rank of foreign Kings? Let’s not exaggerate. But it is a fact that at least one of those sovereigns actually was a King (of Bohemia), who ranked as equal to the neighbourly sovereigns.

|

| The Estates of the Holy Roman Empire in H Schedel (1493), Nürnberger Chronik Artist: Michael Wohlgemut Source: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek |

Even this lofty group of potentates was subject to an internal rating system. Foremost among its Members were the Prince Electors, consisting of: three highly elevated Prince Arch Bishops; one King (of Bohemia); one Duke (of Saxony); one Count Palatinate (near Rhein) and; one Margrave (of Brandenburg). Their exquisite status is indicated by them having to be addressed with “Your Royal Highness”. Together they formed the Chamber of Prince Electors in the Imperial Diet (Reichstag), the foremost decision unit in the Empire.

One step below we find the “normal” Princes: the Prince Bishops; the Dukes; and the Margraves together with other Comital Highnesses of ancient pedigree. Their address was “Your Serene Highness” and they formed the Chamber of Imperial Princes, wherein they held one vote each.

Stepping down another, but very strategic step, we find the last and most numerous excellences still to be counted as high nobility. These were the Imperial Counts and Prince Abbots. The address of the former was “Your Illustrious Highness”. They no longer warranted one vote each in the Diet. The Counts held, collectively, four votes in the above Chamber of Princes, whereas the Abbots held only three.

Readers, wise to wordly affairs and the strivings of men, will realise that there always was some rotation between these groups of nobility. To rise to the status of Prince Elector was virtually impossible, unless you inherited or acquired the territory in question. In contrast, the status of Imperial Prince was slightly more accessible, but only for Imperial Counts. Still, rarely did one of these lower nobles manage to take this step up the ladder of prominence.

Imagine that you are a young Imperial Count born towards the end of the sixteenth century. What would it take to give you at least a sizeable chance to achieve princely status? Keep in mind that the Emperor could only nominate a person to such elevation, the final decision was made by the Chamber of Princes in the Diet.

Firstly, pedigree is of great importance. Just as modern day old money is eager to keep out the “nouveaux riches” from its societal nest, venerable nobility hated to see upstarts among its ranks. A venerable lineage will of course be most suitable. But, to a certain degree, embellishing your residence and make it look like a Ducal Palace with trimmings, may go a long way of at least pretending. In addition, why not have a scribe produce a chronicle of venerable lineage, taken out of thin air, if not attested by family documents?

Secondly, the family territory has to be of a certain size. If our count only owns a domain that you can walk through in a couple of hours, this will certainly not do. It will take at least the size of latter day Liechtenstein to underpin your claim to reign it as a Prince.

Thirdly, you must render services to the Emperor, important enough to render you indispensable to him. Either directly, e.g., through winning battles for him or helping him win the throne from his brother, or indirectly, e.g., through being related to a potentate whose support the Emperor eagerly seeks.

Fourthly, and necessarily, your wealth must be immense; not only to finance your services to the Emperor, but also to win the favour of strategic Members of the Chamber of Princes, so that enough votes for your elevation can be won.

An esoteric subject to embark upon in this blog, you may think. Still, it is important as general background to understand the life and strivings of a noble Emser from the fourth generation, that is, a great grandson of Merk Sittich I, grandson of Wolf Dietrich and son of Jakob Hannibal I von Ems. Upon him fell the chore to achieve what his forefathers had laid the ground for, but failed hitherto to attain: the inheritable status of Imperial Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. A lofty ambition indeed for the Landesherr of the Emser domain, a diminutiv territory on the border of the Alpine Rhine!

|

| Imperial Count Kaspar von Hohenems Artist: Lucas Kilian (1618) Source: Schweizerisches Landesmuseum, Zürich |

Kaspar was the son of Jakob Hannibal I (1530-1587), the last of the three valiant Emser Warlords (see Fortes Fortuna Adiuvat and Magister Militum). As a toddler, and somewhat later, he proved eager to emulate his fierce father, always prone to prancing around the fortification of Hohenems with play sword and bow. His parent, mostly absent on foreign campaigns, was of course delighted and had a child armour, complete with small weapons, fashioned for him in Nürnberg, at considerable expense.

|

| Child armour Source: Ambras Palace |

The child was supposed to grow into that steely corset, on his way to becoming a worthy successor of three generations of fierce warlord. To his father’s regret, he soon turned out quite the opposite: a pious and docile youngster, eager to embark on intellectual quests. No doubt, it was the influence of his pious mother Hortensia that caused it, not to forget her brother, the saintly Cardinal Carlo Borromeo (see God’s Fiercest Champion), who also took a keen interest in Kaspar’s upbringing.

The mother died already in 1578; but Jakob Hannibal acquiesced to her dying wishes and sent off both Kaspar and his two years younger brother Merk Sittich IV (1575-1619) to Milan, to be educated under the caring tutelage of Carlo Borromeo, who was Archbishop in this splendid capital of Lombardy. Perhaps, the father nursed the hope that at least his youngest son, Wolf Dietrich II (1577-1604), would eventually grow into the armour. In vain, as it would turn out.

The two brothers went to school in the famous Collegio dei nobili, destined to educate young noblemen. Kaspar's father still sought to embellish the boy's upbringing further by taking him along on a “Grand Tour”. In 1584, he fetched Kaspar in Milan and travelled with him via Genua to Spain, to pay a visit to the Royal Court in Madrid. Jakob Hannibal, Spanish Prince (Grande) as he was, had business there, since the Crown owned him and his regiment the princely amount of more than 270 000 Gulden, for the Commander's last campaign in the Netherlands (see Fortes Fortuna adiuvat). Alas, no payment was forthcoming; thus, an important lesson in the (un-) trustworthiness of sovereigns was taught the youngster.

|

| Divertissement at Philip II’s Court in Madrid Artist: Luigi Mussini (1871) Source: San Donato Museum, Siena |

Upon their return to Milan, via Rome, both were saddened to see Archbishop Carlo Borromeo on his deathbed. Kaspar would receive some final blessings whispered into his ear and grasp the saintly tutor’s hand just before his death, which would leave a lasting impression on the earnest boy. He was to stay at the College in Milan until 1587 and matriculated at the University of Siena the same year.

But his ambitions to acquire a sound basis in jurisprudence at this learned institution came to nought. In December the same year, his father died unexpectedly, only 57 years old, leaving his 14 year old boy as the main heir to his estate. The following years were a difficult and tricky time for the new head of family. Two sisters had to be wed off with a comital dowry, prescribed in the testament, and an illegitimate sister to be “wed to Jesus”. His estates also threatened to be quartered. A cousin twice removed, Hans Christoph von Ems, held alrady the Emser domains North of Hohenems (Lustenau, Wildau and Haslach) and his two younger brothers, Merk Sittich IV and Wolf Dietrich II, had legitimate claim on the remainder.

To Kaspar’s great luck, his main legal guardian turned out to be his uncle, Cardinal Merk Sittich III von Hohenems. This Croesus among Cardinals (see Celestial Protection), a rather frugal and crafty investor, took great care to educate his ward in the art of managing and augmenting a noble estate. They were rarely to meet in person, but a lively correspondence between the two (still preserved) bears witness of the salient influence the wealthy tutor had on his charge. As a result, all dowries were paid out as prescribed and the estate was managed so as not too unduly diminish its resources.

|

| Cardinal Merk Sittich III, Guardian of Kaspar von Hohenems Extract from Hohenemser Festtafel (1578) Artist: Anton Boys |

During the first thirty years after Kaspar’s coming of age (majority), the Alpine Rhine region, as well as Europe at large, was in a state of uneasy peace and calm. Lombardy, the Italian region to the South had been pacified under Spanish rule after the Great Italian Wars. The Eidgenossen had at long last accepted to stay contained within the Alpine and Upper Rhines. The Eighty Years’ War in the Netherland had come to a delicate truce period. A fragile calm also reigned within in the Empire, after the Religious Peace of Augsburg (1555). Kaspar, the young nobleman, thrived in the absence of violent conflicts, deploying his best faculties as pious, peace loving, frugal and utterly successful squire of his estates. Move by move, he advanced his position in the Empire, never losing sight of the ultimate goal: to raise the House of Ems to Princely status.

Already at the “mature” age of fifteen, he took steps to befriend Archduke Ferdinand II, the ageing ruler of Tyrol and Further Austria. This was important, since Kaspar’s father had greatly antagonised the ruler, to the point that a feud was imminent between the two (Fortes Fortuna adiuvat). As a first gesture of friendship, he extended a loan of 30 000 Gulden to this always specie-hungry Count of Tyrol. This raised the ire of Kaspar's guardian, the frugal Cardinal, who severely admonished him “You stupid young fool, never again lend money to a sovereign without security!”. But Kaspar knew what he was doing; in fact, he had bought himself in to the Archduke’s service; already the year after, in 1589, he was given the position of Kämmerer (Chamberlain) at the Court in Innsbruck.

|

| An ageing Count of Tyrol and his successor Archdukes Ferdinand II and Maximilian II |

Thereafter, no more money without security. Soon he received, as collateral for further advances, the pledge liens of Neuburg and Montfort Tosters, two small domains not far from his own, these loans amounting to just petty cash for the spendthrift Count who lusted for much more. Alas, substantive specie would not be forthcoming from the frugal Chamberlain, unless a substantial pledge was granted. So, Ferdinand, hoping for new large sums, promised Kaspar the Vogtei (governance) of the first large Habsburg domain that would become available in Vorarlberg. Unfortunately, he died already in 1595 without being beholden to his pledge. With this ended Kaspar’s time of Chamberlain at the Court of Innsbruck. Disillusioned with the superficial glamour of the Ducal household, upheld by ever increasing debt, he chose to make his fortune henceforth as ruler of his own domains.

The death of Ferdinand did not hold back Kaspar in his territorial ambitions, however. He took great care to always remind the Archduke’s successor, Maximilian II of the promise given by his forerunner. Still, he dad to wait more than ten years for a response. In the mean-time, he was busy embellishing his home domains of Hohenems and Lustenau.

In his mind, he already saw himself as princely sovereign over the lower Alpine Rhine. Does it surprise you that he set out to turn his small domain of Hohenems into a splendid residence, in fact the only sovereign residence on all of the Alpine Rhine? Thus started the “Gründerzeit” of the Hohenemser, a hectic period of activities that started in 1604 and went on for a bit more than ten years. In short order, the Palace (built by his uncle the Cardinal) was greatly enlarged and embellished, a Baroque palace garden laid out in all splendour, a guest mansion and garden pavilions built therein, and a large Tiergarten (Zoological park) created, which extended all the way down to the river Rhine.

|

| A residence worthy a Prince – Palace grounds of Hohenems Artist: Hans Noppis (1613) Source: Museum Carolino-Augusteum, Salzburg |

In this building frenzy, Kaspar was greatly supported by his brother Merk Sittich IV. The latter was by now well advanced in his cleric career and held amply rewarded sinecures at three Bishoprics, in Constance, Augsburg and Salzburg. Like his brother, he had a keen interest in embellishing the family estate, so as to underpin his own princely ambitions, and he contributed largely with his own funds.

On the brother’s initiative, the settlement of Ems, earlier more like a hamlet, was upgraded to a modern time market place. Northward from the Church, a long straight street was laid out, called Dompropsteigasse (Street of the Provost) where building plots were made available without charge to artisans and merchants, to establish themselves as free citizens (burghers) in the domain. From near and far, small entrepreneurs followed the call and soon the market place was booming with business activities. Even a paper mill and a printer were established, the first book printer ever on the Alpine Rhine.

This newly fledged economy needed appropriate finance and merchandising activities to keep it expanding. To that effect, the Count invited a Jewish community to establish itself in the settlement. A special charter was created to accommodate this foreign element in Hohenems, granting it self-governance, with the right to build a synagogue, a ritual bath, a school and a poorhouse. Soon, this small state-within-the-state was firmly rooted in Emser soil and became an integral part of the market for centuries to come.

|

| Charter issued by Count Kaspar in 1617 for the newly established Jewish Community Source: Jüdisches Museum, Hohenems |

Also culture and education were to be promoted: a latin school was founded and the comital library, already begun by his father, greatly enhanced. Also tourism was encouraged, by refurbishing and enlarging a well-known and venerable mineral spa in the neighbourhood. All in all, the Count excelled in promoting his estate, rather than in accruing wealth through warfare and plunder. In that he was ahead of his time; the era of enlightened sovereigns would come first about a century later. A princely residence indeed had been created by Kaspar, albeit without a territory worthy a Prince. The Count now went about acquiring the latter.

Finally, in 1607, Maximilian II, Ruler of Tyrol, remembered his forbearer’s commitment and endowed Kaspar with a major Vogtei (governship): the territory of Bludenz-Sonnnenberg, a large domain at the far South-East of Vorarlberg. This was not an ideal extension of the Count’s estates, since it was quite disjointed from his own properties and, furthermore, rather unruly to govern.

It took fully six years before another opportunity arose. An ailing Count in financial difficulties, Karl Ludwig zu Sulz (1560-1616), was looking for a buyer for his domains of Schellenberg and Vaduz. This was a large territory West of Bludenz-Sonnenberg, encompassing almost half of the Lower Alpine Rhine Valley. The Abbey of St Gallen and the Habsburger both lusted for the Count's dominion and were prepared to pay at least 220 000 Gulden for it. Kaspar managed to out-manoeuvre his competitors by combining his offer with the offer to marry Count Karl’s daughter. So it came to be: he acquired the estates at the more reasonable sum of 200 000 Gulden and married Anna Amalia von Sulz (1593-1658) the following year.

|

| Count Karl Ludwig zu Sulz, High Official at the Imperial Court Source: Landesmuseum Württemberg |

Having thus greatly enlarged his territory, Kaspar next cast his eyes on a dominion closer to his own of Hohenems and Lustenau. This was the County of Feldkirch, a Habsburg owned Imperial lien, which, if falling into his hands, would link the above territories with those of Schellenberg and Vaduz. As a result, a contiguous stretch of the Alpine Rhine, in fact almost all of its lower part North of the Luzier Steig, would fall under Emser governance.

It took considerable efforts to achieve this goal. Kaspar’s financial position was not ample at the time, the horrendous sum of 200 000 Gulden having been spent on Schellenberg and Vaduz. It wold be achievable only if he could switch the Vogtei of Bludenz-Sonnenberg against Feldkirch. Maximilian II was reticent. In his view, Kaspar had mismanaged the governance of Bludenz. Neither were the Estates of Feldkirch favourably inclined; they still remembered his forbearers’ high handed governing, running rough-shot over the subjects’ acquired rights.

But Fortuna came to the rescue once again: In 1612, his brother Merk Sittich finally achieved the ultimate goal: to be elected Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, the most prestigious church position in the Catholic domains of the Empire. The newly elected put his prestige behind Kaspar’s demand and this decided the issue; the Vogtei of Feldkirch fell, in 1614, to the Emser as an inheritable pledge.

|

| Territories on the Alpine Rhine under Emser administration in 1614 |

With this, major steps towards obtaining Princely status had been taken. We almost can feel the jubilance that must have reigned in the Emser residence. In coming years, a range of actions would be set in motion by the Count and the Prince Archbishop to “close” and elevate the House of Ems to high Imperial glory.

-o-

I see that this tale has begun to live its own life, getting ever longer. Best to lighten it up with an intermission here, and let you in on its dramatic finale at fortcoming blog posts.

Comments

Thanks so much for sharing with me your link to the Sacrum Imperium Romanum and to your grand-grand-grand-grand, etc. etc. ancestor Kaspar. Reading that was a total delight. What fun!

Hope you're keeping safe. Best wishes from Berkeley,

Alan

Jiří Brnovjak