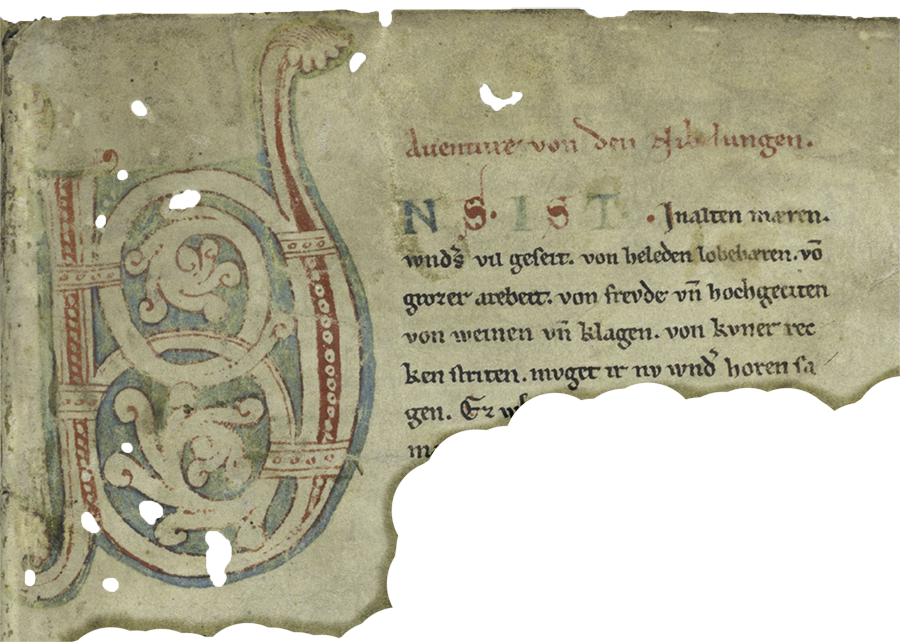

Maximilian’s last Triumph

|

| Verkünder des Triumphs (Herold proclaiming the Triumph) Colorised Woodcut Der Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians (1526, 1765) Artists: Burgkmaier/Höfer Source: Universitätsbibliothek Graz |

I am sitting at my kitchen window, looking out into the dark and humid fog in this late hour of New Year’s Eve of 2023, and musing about things in general, in particular, life and the meaning of it. It occurs to me that most of what I have accomplished during my years of existence is already slipping away into oblivion, like sand running through the narrows of the hourglass.

What will be left of me when I am gone? What of all the work projects I have been so busy with all my life? The only people still vaguely remembering me are those of my own age, who will soon be gone as well as I will be. The others see an old totterer stumbling on the icy and sluicing sidewalks on his way to the coffee shop, maybe feeling sorry for his faibles, but having no idea about the man they just met.

However, there is hope amid this despondency. Have I not published three books in my lifetime, oeuvres that will survive me and rest forever in the safe vaults of the Royal Swedish Library? Indeed, a way to survive my demise, so to speak, to stay immortal! Lest you think me an old fool to console myself with this revelation, let me tell you that I am sharing these thoughts with men far more significant than me and with a real afterlife in mankind’s collective memory! So, on with a story that has kept me intrigued and busy lately, which I trust will also interest you, Dear Readers! It played out about five hundred years ago and has as its main subject a Roman Emperor of a sort.

|

| The Innsbruck Residence of an aging Emperor Artist for both pictures: Albrecht Dürer Sources: Albertina and Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien |

This time, he was on his own, with only minimal support from the French. Now, failure loomed large over this new foray! For the entire month of September, his main army besieged Padua, the main city on the Venetian mainland. Storming upon storming led to nothing but decimating his troops. Finally, he even had to ask the French heavy cavalry and his own to dismount and assist the landsknechte with the assaults, since precious few foot soldiers were left alive. The cavaliers categorically refused to do so. With no success to be had, his war chest being empty, and winter approaching, nothing left to do for Maximilian but to return home to Tirol in dishonour with the sorry remainders of his men.

|

| The Venetian campaign of 1509: In the beginning a success – eventually a disaster! Triunfo del Emparador Maximiliano Source: Biblioteca nacional de Espagna |

Miserable as he was, in his chambers in Innsbruck, his musings got more melancholic by the minute. It seemed as if life was already slipping away, and death was beckoning him with bony fingers. Will the recent misadventures colour my aftermath when I am gone, he wondered? Will I forever be known as the ruler unable to reach the ambitious goals he has set for his reign? A failure of an Emperor, a bad example for the history books? What will my grandchildren and their descendents think of me? Will they not follow the bad example of their forefather in his dotage? Will all the good I have accomplished in life be forgotten as soon I am gone, overshadowed by the misadventures of my later years?

“Wer ime in seinem leben kain gedachtnus macht, der hat nach seinem todt kain gedachtnus, und desselben menschen wirdt mit dem glockendon vergessen,” he quietly mumbled to himself. He, who does not make a name for himself in this life, has no afterlife and will be forgotten as soon as the bell tolls for him.

It all had started off so well for Maximilian when he was still in his teens. After the timely death of a fierce warrior, Charles the Bold, the youngster won 1477 the heart of the Duke's daughter, Mary of Burgundy, the wealthiest bride in Europe. Some ten years later, Sigismund of Tirol abdicated from his throne, and Maximilian took charge as Count of Tirol and ruler of the Austrian Forelands. With the combined riches of Burgundy and Tirol combined, he could fund an army to reclaim the Austrian provinces from the Hungarians in 1490. Finally, Vienna became a Habsburg city once more! Even the Crown of Hungary, promised the Habsburger already back in 1463, seemed within his grasp.

|

| Maximilian marries Mary of Burgundy in 1477 Triunfo del Emparador Maximiliano Source: Biblioteca nacional de Espagna |

After another successful campaign, in 1504-1505, this time against the Palatinate Bavarians and the Bohemians, he managed to round up his County of Tirol with the great cities of Kufstein and Kitzbühel, as well as Schwaz, the site of the most significant silver reserves in Europe. Already before that, in 1500, he inherited Eastern Tirol and Görz from the last Count of Görz.

|

| The siege of Kufstein in 1504 Triunfo del Emparador Maximiliano Source: Biblioteca nacional de Espagna |

His most notable achievement was securing rich consorts for himself and his descendants. Following Mary’s untimely death in 1482, he arranged for his child daughter Margareta to be wed to the Dauphin in 1483 to warrant peace with France. In 1494, he himself married Bianca Sforza, a niece of the reigning condottiere in Milan. This marriage significantly embellished his coffer and led to the reintegration of the large region of Milan into the Empire, by reinstating it as an Imperial Duchy with Ludovico Sforza as Duke.

He orchestrated a marriage between his son Philipp and the Spanish Infanta Johanna two years later. This alliance had the potential to grant the Spanish Crown to the House of Habsburg, which already possessed Burgundy and an enlarged Austria. By acquiring Spain, Habsburg could become the most prominent royal house in Europe, he hoped.

|

| Philipp marries Johanna of Spain in 1496 Triunfo del Emparador Maximiliano Source: Biblioteca nacional de Espagna |

As Ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, he was instrumental in reforming the legal structure and administration of this somewhat unruly body of a state. He came into office after the demise of his father, Fredrik III, in 1493. Soon after, he called for a general assembly of the realm’s dignitaries, the Imperial Diet of Worms (1495). His main focus was to achieve a more unified country out of this greater Germany, just like France, Spain, and England had been brought under one banner in the previous century.

After enormous wrangling with the notoriously independent Imperial Princes, a distinctive step towards this goal was taken at this Diet with a package of reforms. These include, above all, the Perpetual Public Peace (Ewiger Landsfriede), doing away with the never-ending feuds between high nobility, the Imperial Court of Justice (Reichskammergericht) for settling legal issues within the Realm, and the Imperial Common Penny (Gemeiner Pfennig), a wealth tax to be paid by his subjects, one and all, even nobility.

|

| The Court of Justice in session in Wetzlar Copper engraving (1750) Source:: Städtische Sammlung Wetzlar |

As these successes grew, so did his ambitions. He increasingly saw himself as the Universal Ruler of Europe, destined to lead the continent in a massive crusade against the Anti-Christ lurking in the East. With the prospect of peace at home, a steady stream of state income, and the revenues from his vast family domains, he certainly could finance a massive army, he imagined, eliminate the Ottoman threat once and for all, and reclaim Constantinople for Christianity! At long last, Imperator Maximilianus Magnus would make the Empire of the Romans whole again, like a latter-day Justinianus the Great, who had set him a shining example a millennium afore! Alas, ambition, ambitions, great expectations ...

So, why these melancholic concerns of Maximilian about his legacy? Wasn’t he one of the most successful and powerful Rulers in Christianity?

|

| Germania (symbolising coronation as King of Germany in 1486; right) and Holy Roma (Coronation to Emperor in 1508; left) Triunfo del Emparador Maximiliano Source: Biblioteca nacional de Espagna |

Not so fast! The Goddess Tyche is a capricious dispenser of ill as well as good fortune. For every bit of success we managed to quote so far, there is a host of drawbacks and disappointments to account for, if we are to do justice to Maximilian’s life. One step forward and two sideways or backwards seems appropriate to describe Maximilian’s career as sovereign.

The misfortunes of the Emperor began soon after he got married to Mary of Burgundy. Just five years later, Mary died unexpectedly in a riding accident after having given birth to both their children, Philipp and Margareta. The Estates of the Netherlands were not happy with Maximilian as regent for his son; uprisings occurred off and on for almost twenty years, binding a large amount of troops and resources to maintain Habsburg ownership. In addition, France claimed that a major part of Maria’s possessions were French liens and demanded them back, starting a war concurrent with the Burgundian uprisings. After twenty years of continuous struggle, with fortune upon fortune lost in battles and subduing the uprisings, Maximilian was forced to hand over almost a third of Maria’s dowry to France at the Peace of Senlis (1493).

|

| Overpowering the first Flemish uprising Triunfo del Emparador Maximiliano Source: Biblioteca nacional de Espagna |

Both his marriage arrangements with France came to nought. In addition to marrying his daughter to the Dauphin, he himself married, in 1491, Anne of Bretagne, to force France to peace. No success story there! The Dauphin, recently having succeeded his father as Charles VIII, annulled his marriage with Margareta and forced Ann of Bretagne to marry himself instead (her marriage with Maximilian had not yet been consummated)! An enormous affront from a brother-in-reign!

During his marriage negotiations in Spain, Maximilian had to make a promise to King Ferdinand of Aragon to help him defend his right to the Crown of Naples against any French claims. This promise eventually dragged Maximilian and the Empire into the Great Italian Wars, which would outlast the Emperor and go on for another 40 years. Additionally, just two years after Philipp ascended the throne of Castile in 1504, he passed away suddenly, leaving it uncertain if any of his descendents at all would be accepted as the future King of Spain.

|

| Military support to the Kingdom of Naples in 1501 – successful but costly! Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians I Source: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek |

Re-establishing Milan as an Imperial Duchy following Maximilian's marriage to Bianca Sforza was also in vain. Barely four years after that, the French conquered the Duchy and held Duke Sforza henceforth captive in France. Milan was reaped from the Empire for good, never to return as Imperial Feoff! And Maximilian’s uncle-in-law would waste away in French dungeons. What an affront!

Even Maximilian’s Hungarian prospects evaporated (for the time being). After having regained control of Austria from the Hungarians, following Mathias Corvinus’ death in 1490, Maximilian forged into Hungary to secure the St. Stephen's Crown, promised the Habsburger in the Treaty of Ödenburg already thirty years before. His campaign was initially successful, and even the olden royal capital of Stuhlweissenburg (Székesfehérvár) was conquered (and plundered). Still, the campaign had gone on too far into autumn, and the war chest had been emptied, so the troops refused to continue fighting, and a zealous warrior had once again to return home with unfinished business.

|

| The campaign in Hungary of 1490, ending with a miserable withdrawal Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians I Source: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek |

Above all, his grand vision to consolidate a greater Germany, reconquer Constantinople, and re-establish a universal Roman Empire turned out to be a chimaera. The Diet of Worms in 1495 was already sabotaged, with the dreaded Eidgenossen refusing to attend and utterly rejecting the agreements reached therein. No foreign judges would ever be allowed to rule over the Alpine meadows, and the Swiss insurgents would not pay a single penny into the Imperial coffers! Eventually, weaponed encounters erupted between the Swiss and their Swabian neighbours, drawing Maximilian into the conflict. After nine months of fighting in 1499, in the “gruesome Swiss War” (Der greuliche Schweizer krieg), battle after battle had been lost, and the Emperor’s troops gone with the wind; Maximilian was forced to sign a peace that granted the Swiss Confederation exit from the Empire, de facto if not yet de jure.

|

| Der greuliche Schweitzer krieg (The gruesome Swiss war of 1499) Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians I Source: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek |

The example set by the perfidious Eidgenossen inspired, in turn, the Imperial Diet to stay reticent as concerns taxation. Maximilian’s recurring demands for financing a large army to set out against the Ottomans were always categorically refused by the Princes and Cities of the Realm, as was the financing of more regional campaigns in Europe, particularly those carried out in Italy. This forced the Emperor to finance his regional forays out of his private purse, which soon became and stayed empty. Huge personal debts were building up, keeping him in hock to and enriching the German bankers. By his death, the arrears amounted to a full 6 million Gulden, which took his heirs an entire century to clear.

Back to that dreary late November evening at Maximilian’s private chambers in Innsbruck! Melancholic as his thoughts were, he still was a man of action. Determined decisiveness eventually helped him overcome his depression. He simply had to act to remedy the situation. But how? Suddenly, a picture appeared in his head: a stone pillar rising high in the sky like a finger beckoning him to follow. We know this pillar nowadays as Trajan’s column. It has survived almost two millennia and was already well known at the royal courts in medieval times. In Maximilian’s time, an artist called Jacopo Ripanda had described it in all detail in a series of beautiful drawings, which explains its appearance in the Emperor’s mind.

|

| Emperor Trajan’s column Alfonso Chacón, Historia utriusque belli Dacici a Traiano Caesare gesti (1616) after drawings by Jacopo Ripanda (–1516) Source: Brown University Library |

This famous column is clad in a ribbon of solid marble, which spirals upward, depicting the great Roman Emperor’s military conquests. Could you unwind the ribbon and present it in all its length, it would be more than a hundred meters long and around one meter in height. Why not produce such a ribbon myself, thought the determined Maximilian. Maybe not in marble, which would take too long to finalise and be far too expensive, but why not in the form of a scroll (not unlike a Torah) of finest calfskin, on which my greatest accomplishments and the grandeur of the Imperial household could be depicted in splendid colour. The scroll should match Trajan’s ribbon in size and grandeur but appear as a monumental painting instead of a monumental pillar. Thought and done! He immediately called for his privy secretary, Treitzsauerwein, and asked him to set things in motion.

The Secretary then gave Johannes Stabius, the court historian, the task of carrying out the necessary research for the work. It took Johannes almost three years to get hold of all the material for the artwork and prepare a first draft of its content. Based on this draft, Maximilian then personally dictated a final version of his liking to Treitzsauerwein and entrusted Stabius with supervising its execution. The historian was granted a leave of absence and a house in Regensburg to keep the artists involved on a tight leash. The work was carried out by Albrecht Altdorfer and his painting company, consisting of fellow painters, mostly apprentices and journeymen, and it took a full three years, starting in 1512, to get it done.

|

| The researcher (Johannes Stabius) and the painter (Albrecht Altdorfer) Triumphzug Kaiser Maximilians I Source: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek |

The result was marvellous. When unrolled before the Emperor’s scrutinising but soon admiring eyes, a multitude of tableaus had appeared. A herold saddling a gryphon led the procession. He was followed by several groups of men from Maximilian’s private household: hunters, musicians, actors, and mimes; thereupon came groups of jousters that had competed in tournaments with the ruler as young King; after that the first highlight: Maximilian's marriage with Mary of Burgundy; then flag bearers, showing all the domains that the Emperor possessed; thereupon banners exhibiting significant battles and other events in Maximilian’s turbulent life; soon to be followed by a multitude of statues depicting his forefathers.

At long last, heralds announced his triumphant carriage, pulled by fully twelve greys and followed by an escort of Imperial Princes and other high nobles. To round up the whole event, his famous landsknechte came marching and waving banners, together with Maxiilians’s beloved artillery; and, last but not least, a baggage train like that accompanying all landsknechte regiments was winding its way helter-skelter through the countryside as a welcome counterpoint to all the grandeur exhibited in this seemingly endless cavalcade.

|

| Der Tross (End half of the whole tableau) Triunfo del Emparador Maximiliano Source: Biblioteca nacional de Espagna |

Upon seeing all this splendour, Maximilian, never content to rest on his laurels, already began to deliberate how the public could share in the glory of the scroll. Granted, it was a prized possession, but accessible only to a select few at court. All my subjects that count must witness my triumph, Maximilian said to himself. Again, said and done. The Emperor summoned the realm's most eminent painters – Altdorfer, Burgkmaier, and Dürer foremost among them – and commanded that woodcuts be made based on the artwork. It was estimated that about 200 woodcuts would cover the scroll's content, and work got ahead speedily. The plan was to make as many prints of the triumph as there were Imperial cities and Princes in the realm so that the parade could be exhibited in all its length across the Empire.

To our regret, Maximilian died already in 1519, so the work was never finished. Only 147 woodcuts were completed. Never would Maximilian’s triumph be exhibited on the walls of Princely residences and Imperial town halls! At least, the incomplete set was printed and distributed as originally intended by the Emperor’s grandson Ferdinand. The receivers never displayed them, storing them in their archives istead. Most sets were kept as single prints and some few were bound as books. Notably, the sets did not include the triumphant carriage. Dürer, who had created the woodcuts for it, decided to keep them for himself when Maximilian passed away. Later, he printed them as a distinct edition, which was popularly sold throughout the Empire.

|

| Der grosse Triumphwagen des Kaisers Maximilian I Eight prints from woodcuts by Albrecht Dürer (1518/22), composited by the author Source: The Metropolitan Museum |

We may assume that Maximilian’s concerns about his aftermath had been put to rest, once the scroll had been completed. But, did the Emperor's monumental scroll truly establish and maintain his reputation as a great leader? Sorry to say, its impact was almost non-existent. The scroll and the two copies made thereof in the decades after its completion remained ensconced in royal archives. All three were eventually sliced into numerous pieces and then compiled into books. After that, they were eventually stored in museum cellars like Sleeping Beauty, with only an occasional archivist venturing down there and glancing at them with myopic yet admiring eyes. Of the woodcuts, only Dürer's Triumphal Carriage gained fame, thanks to the artist rather than the Emperor with his thirst for glory.

In hindsight, Maximilian need not have worried on that sombre evening in Innsbruck in 1509. Even if his most grandiose plans for a universal Empire proved futile, the concept lived on. For a short period of forty years, his grandson and successor, Emperor Charles V (1500-1558), managed to rule over a realm with global reach, within which the sun never set. But it would not last. Besieged externally by the French and the Ottomans, and internally by religious division, Charles eventually gave in, abdicated, and divided up his realm between his son and brother, thus creating two distinct realms and lines of the House of Habsburg.

The Holy Roman Empire, ruled by the German Habsburg line, was far from prospering in the following centuries and faded away already in the early 1800s during the Napoleonic upheavals. Paradoxically, this would lead to the birth of a new Empire, which ultimately had to thank Maximilian for its creation.

In 1515, the Emperor made a last shrewd and profitable move by entering into his most advantageous and viable marriage agreement yet. During a meeting with the Kings of Bohemia/Hungary and Poland, marriage contracts were settled for the wedding of his grandchild Maria to Ludwig, the son of Ladislas II (the Bohemian/Hungarian King), and one of his two grandsons (to be decided later) to the King’s daughter. Maximilian would never live to see this agreement become a reality. However, in 1526, Ludwig, who was already the King of both his countries, was killed in the Battle of Mohács against the Ottomans. This left his crown to Ferdinand, the younger grandson of Maximilian and greatly embellished the Habsburg domains.

|

| Tu felix Austria nube! (The Habsburger Double Wedding in 1515) Artist: Václav Brozík (1896) Source: Kunsthistorisches Museum Belvedere, Wien |

In consequence, when the seemingly eternal Holy Roman Empire dissolved in 1805, a new Empire consisting entirely of Habsburg domains could emerge like a phoenix from the ashes. The Austrian Empire, a Danubian Monarchy that spanned from the Ukraine to the Adriatic Sea, would outllive Maximilian by fully 400 years. A lasting memory indeed of the Emperor’s diplomatic genius: Maximilian’s Last Triumph!

A VERY HAPPY, PEACEFUL AND SUCCESSFUL YEAR 2024!

Comments

With a cup of tea in my hand on the first morning of the new year I have just finished reading your new history chronicle about Maximilian and at the same time listening to the ritual fire dance of Chatjaturijam (however he spells his name) on the radio. Is it with fire we enter the new year 2024? No but with energy to resist at least some of the difficulties that lie ahead of us. It will certainly not be one of the easiest years to experience, but with positive thinking, the support of family and friends, happy events to remember, good literature and not least (in my case) lovely uplifting classical music that gives you strength we will endure. The weather will be miserable and the streets in our area badly looked after but there will be highlights in our lives even this year! Maybe a splendid spring day or a glorious summer day, who knows, but I am sure they will come for all of us.

With these lines I would like to thank you, Emil, for all the encouraging chronicles on your blog, it is each time a new interesting history lesson, and wish you and your readers of this blog a prosperous new year!

Kind regards

Eva

Du förgyllde min nyårsdag med din fina berättelse om Maximilian och dina funderingar i anslutning till den.

För egen del är jag mer upptagen av hur leva det som återstår av ens liv på ett någorlund värdigt och inressant sätt. Mer än av eftermälet. Det är heller inte en enkel fråga.

Vi grubblar väl vidare.

Gott Nytt År!

Åsa

Have a good healthy year and enjoy every single day.

Best regards Bharat

För så fint epos, har inte mer än tittat på bilderna som jag oxo först gjorde i historieboken i skolan, men fint är det. Jag kommer att fortsätta studera det. Hoppas du får ett mycket, mycket fint 2024.

Kari

En varm välgångsönskan med nya historiska utflykter önskar vid Dig!

Åsa och Richard

I am humbled by your words of praise and good wishes. This will most certainly help me to get thhrogh the coming year. And, Richard, you are so polite as calling me chronicler! To thank you, I have located the portrait of Maximilian that you have been missing. It occupies now a prominent place right in the beginning of the blog.

Yours sincerely

Emil

Hallo Emil, ich hoffe, das neue Jahr hat für dich gut begonnen und geht auch so weiter.

Deine historische Darstellung über den Traum alter Männer irgendwie erinnert zu werden, spiegelt auch mein altersbedingtes Gefühl wieder und erinnert mich an die Zeit, als ich vor der Trajanssäule in Rom stand. Aber die Säule hatte bei ihrem Bau eine symbolische Funktion und war bunt bemalt und mit Metallwaffen ausgerüstet. Heute sehen wir die Steinreliefs in guter Handwerkskunst die ihre Pracht in einer feinen Steinarbeit und Bauarbeit mit ausgezeichneter Festigkeit zeigen, galt meine Bewunderung diesen Steinbildhauern mehr als Trajan und dem Römischen Reich. So war es auch bei Maximilian in deiner Geschichte; Alle bewundern Albrecht Dürrer.

Mit anderen Worten: Es ist nicht einfach, auf zeitlos nachhaltige Weise in Erinnerung zu bleiben.

Herzliche Grüße aus Lustanien, die letzte Blume Latiums

Michael

Deine verdienstvolle Abhandlung der Machtansprüche des historischen Potentaten Maximilian hat mir wiederum das Glück von uns Zentraleuropäern bestätigt, in eine humanistisch demokratische Geschichtsperiode hineingeboren zu sein. Dabei hat doch auch schon Maximilian über ein christliches Erbe verfügt, das leider auch im heutigen globalen Zeitgeist vielfach nicht erkennbar ist, und doch: ein wenig Modell sind wir Europäer vielleicht für die Welt mit unseren Vorgaben unseres Europarates!

Danke für Deine Einladung zum Reflektieren. Auf alle Fälle hast Du und die Emser ein bestehendes Denkmal in der österreichisch-vorarlbergerischen Stadt Hohenems.

In freundschaftlicher Verbundenheit Heinz

Ich habe deine historische Abhandlung über Maximilian aufmerksam studiert, wäre ich Tiroler, würde da das Denkmal Maximilian vom Thron geholt.

In letzter Zeit waren auf „ARTE“ – Dokumentationssender der ARD + ZDF, und im ORF der Werdegang der Habsburger von den Anfängen auf der Habsburg in der Schwyz bis 1815 – Ende des Wiener Kongresses und der Neuordnung Europas in etlichen Folgen gezeigt worden, z.T. mit Schauspielern in kurzen Sequenzen veranschaulicht, der überwiegende Teil von Historikern beleuchtet und entgegen den „Märchen des Werdegangs“ der Habsburgern in der Österr. Geschichtsschreibung richtig gestellt, ich kann mich noch an den Geschichtsunterricht in meiner Gymnasialzeit erinnern, Maximilian der letzte Ritter und die geschichtliche Verklärung dabei.

Interessant, die Habsburger haben die Maxime der mehrfachen Verheiratung ihrer selbst in z.T in mehreren Ehen und auch der Kinder und Verwandten zur Absicherung, Zugewinnung von Besitztümern und Einflussbereichen bereits eingesetzt, als sie noch nicht einmal Grafen waren, also alles vor 1000 noch in der Schwyz und dem Elsass, Burgund und dem heutigen Baden-Württemberg.

Daraus wurde im Laufe der Jahrhunderte „TU FELIX AUSTRIA, NUBE!“

Zum Fluss Neretva – die Großcousine meines Vaters, in Belgrad als Tochter eines K&K Militärarztes geboren, hat bei ihrem Studium in Belgrad einen Kroaten aus Ragusa/ Dubrovnik kennengelernt und geheiratet, eine Villa direkt mit Blick auf Ragusa gehörte der Familie ihres Mannes, beide Ärzte waren kein Parteimitglied der Kommunisten in Jugoslawien, daher auch nur Privatärzte.

Liebe Grüsse

Jürgen

Mit viel Freude und Interesse habe ich Deine Ausführungen zu Maximilians Leben und Wirken gelesen. In so großer Klarheit habe ich diese für unser Land so entscheidende Persönlichkeit noch nie beschrieben bekommen. Interessanterweise waren mir die „Siege“ von Maximilian viel näher im Gedächtnis als seine vielen schweren Niederlagen im Lauf seines nicht allzu langen Lebens. Seine an den Anfang gestellte Bekümmernis war wohl nicht berechtigt, wie die Geschichtsschreibung über Jahrhunderte berichtet, jedenfalls muss er eine außergewöhnliche Persönlichkeit gewesen sein, die weit über sein Leben hinaus wirksam blieb. Viele Errungenschaften aus seiner Zeit haben lange Wirkung gehabt und offensichtlich hatte er auch gute Berater und Mitstreiter – die Emser waren wohl immer dabei!

Nach der Lektüre Deines hervorragenden Berichts ist mir so richtig zu Bewusstsein gekommen, dass natürlich auch Persönlichkeiten wie Putin, Xi und Biden von Visionen und Sachzwängen beherrscht werden, wie zu Maximilians Zeiten. Auch sie alle wollen „in Erinnerung< bleiben“ und ihren Einflussbereich absichern oder erweitern. Sicherheit und Frieden sind auch eng miteinander verzahnt -Sicherheit braucht Macht und Verteidigungsbereitschaft, allerdings auch rasche Anpassung an alle neuen Entwicklungen, ein Ausruhen auf den Erfolgen vergangener Zeiten ist ein erste Zeichen des Machtverlustes – wie kann die EU mit diesem Problem fertig werden?

Es gibt offensichtlich Grundgesetzmäßigkeiten der Politik, der sich kein Potentat einfach widersetzen könnte. So ist leider offenbar der Krieg als Weiteerführung der Politik mit anderen Mitteln (Clausewitz) nicht auszurotten. Ukraine und Israel sind Stellvertreterkriege, so wie Maximilian viele geführt hat. Der Unterschied zu damals ist wohl die heutige Unterstützung von Politik durch Kommunikation in Echtzeit und global, das war zu Maximilians Zeiten noch nicht so möglich.

Danke für Deine Arbeit an der Geschichte – unserer Geschichte!

Und alles Gute für das Neue Jahr und weit darüber hinaus.

Helmut